22 Dec 2023

Engineers bring something unique to the top tables of businesses, non-governmental organisations, government agencies and academia in Aotearoa, from problem-solving skills to pragmatism. So, what makes engineers good leaders, why should they step up to leadership roles, and what guidance is available?

Alison Andrew FEngNZ remembers vividly the moment her path forked. It was the middle of the night, deep winter, northern Germany, and the University of Auckland engineering graduate was chasing down an argon leak on a cold box.

“I was standing on top of this structure in my Michelin overalls, it was cold, the sea was ice, and I thought ‘What the hell am I doing?’”

A nuts-and-bolts engineering career froze on the vine that night in 1986. Within a couple of years, Alison had completed an MBA with distinction at the University of Warwick and embarked on a life in business that culminated nine years ago in her appointment as CEO of Transpower. It’s a hefty responsibility, heading the entity that operates the national grid, but it’s entirely in keeping with a career that has included senior leadership roles at Fletcher Challenge, Fonterra, and mining and infrastructure solutions provider Orica. She is also highly experienced in governance, as a Director for Port of Tauranga and CIGRE, and was a Director for Genesis Energy.

Transpower CEO Alison Andrew. Photo: Transpower

Leading high-performing teams is what gets her out of bed in the morning.

“You get to attract, develop and grow great people, and that’s quite a unique thing – and a real privilege,” she says.

There’s no overwhelming evidence that engineers are over-represented in the leadership stakes in this country, but they more than hold their own. Scan the academic credentials of corporate directors and executives, and you’ll find plenty of engineering degrees. Similarly with academia, public service and politics. Public figures with engineering backgrounds include business leaders and entrepreneurs such as Rob Fyfe CNZM DistFEngNZ, Rocket Lab's Peter Beck, businessman Chris Liddell CNZM, ACT Party Leader David Seymour and mayors Wayne Brown and Nick Smith FEngNZ.

Leadership is only one aspect of engineering’s value to New Zealand – a recent PwC report shows engineering contributes between $14.6 and $18.1 billion every year to GDP – but it’s not inconsequential. Engineers bring something unique to the top tables of businesses, non-governmental organisations and government agencies.

“I tell people I was programmed at university. They look at me like I’m saying something evil, but it really is a way of programming you to think in a certain way,” says Alison.

“Engineers bring problem structuring, problem solving, logic and pragmatism.”

“Have a go”

Alison says one of the biggest curveballs in her career was when she was offered the position of Finance Director for Fletcher Challenge Paper, after successful leadership roles in the company’s energy and forestry businesses.

“The head of Fletcher Paper rang and said ‘I want you to be my CFO.’ I said ‘I think you have the wrong Alison; I’m an engineer.’ He said ‘That’s exactly who I want as my head of finance.’”

Of course, she took the job. It’s one of her pieces of advice to any young engineer contemplating stepping up to a leadership position.

“Have a go. Because otherwise how do you know what you’re good at, or what you like doing?” She adds that she wants to see more engineers take the leap.

“A lot of the jobs of the future are going to be in STEM, so being a role model for young people is important. And engineering is such fantastic training because you can go in so many directions, from chief executive of a business to a technical expert to a project director running amazing projects.”

Having said that, the engineering mindset isn’t enough on its own to lead at the top level.

“It’s a really important perspective, but like any perspective on its own, it’s insufficient,” says Alison.

“You also have to possess or develop EQ [emotional intelligence] and people leadership skills. You have to like working with others and to find it interesting to develop and grow teams, and you need to surround yourself with people who bring diverse perspectives and to build on those.

“At Transpower, we do a lot of work behind the scenes to keep the lights on, and that requires really smart technical people. But the key is to get them working with all the fantastic people in property, environmental resource consenting, legal, commercial and customer service. It’s all about getting people working together.”

Empowering the next generation

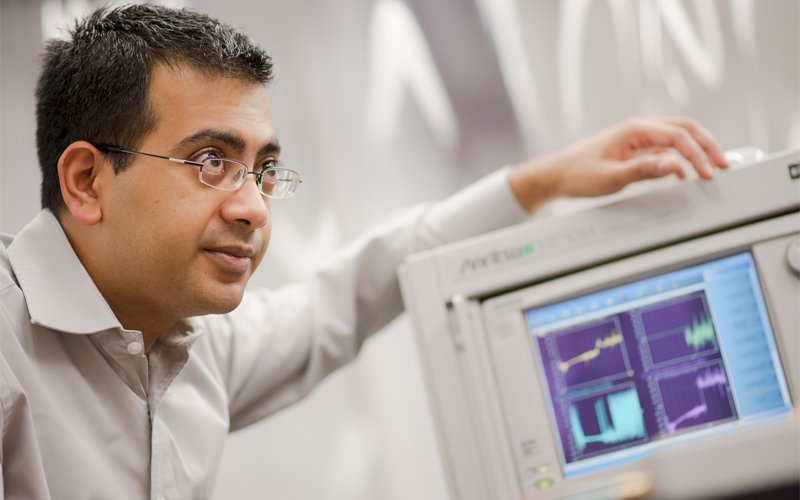

For Professor Saurabh Sinha CMEngNZ CPEng, leadership is all about raising up others – or as he puts it in an online self-profile, “my mission is to leverage my expertise and network to empower the next generation of engineers and researchers”.

There’s plenty to leverage. Recently appointed as Executive Dean of the University of Canterbury’s Faculty of Engineering, Saurabh is an authority on the application of mm-wave integrated circuits for 5G and 6G telecommunications. But he also has international pedigree as an academic and industry leader, with his previous roles in South African universities including time as an institute director, executive dean and deputy vice chancellor for research and internationalisation. Additionally, he served as a director at the global level for the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE).

Engineering is such fantastic training because you can go in so many directions, from chief executive of a business to a technical expert to a project director running amazing projects.

Saurabh says his experiences with the IEEE and his exposure to the sustainable development goals changed his thinking.

“What became apparent during my journey within that organisation is that the big problems humanity faces really can’t be solved by a single discipline. You need the thread and weave of multiple disciplines to create the fabric that makes solutions acceptable to society.”

It’s a theme he brings to his role at the University – that as well as technical competency, engineers today also need to apply a social lens to their work – and it informs his view of what engineers bring to leadership roles. Like Alison Andrew, he believes the engineering mindset is valuable and important, but not sufficient.

“You need a blend of engineers with other disciplines in the leadership mix, I think.”

Saurabh Sinha CMEngNZ CPEng at the mm-wave laboratory at the University of Pretoria. Photo: University of Pretoria

What do engineers bring to governance?

According to the Institute of Directors (IoD), the engineering perspective can bring the kind of diversity of thought that helps boards make better decisions.

“Engineers are trained to be problem solvers,” says IoD Chief Executive Kirsten Patterson. “They expect to assess data and reach logical decisions – and this may include working with limited data. Engineers are more likely to understand scientific ideas than people from other backgrounds, and this can bring valuable insights to boards on issues such as climate governance, for example.

“One of the IoD’s top five issues for directors in 2023 is ‘board agility’,” she continues. “That’s another way of saying boards need to find new ways to think and to operate in order to meet evolving governance challenges. They need to be mentally and procedurally agile. It is likely that the perspective engineers bring to the table would help boards to think beyond their norms, and perhaps find ways to operate more efficiently and effectively.”

Using engineering to improve lives

A senior lecturer at the University of Waikato’s School of Engineering, Dr Mahonri Owen MEngNZ’s research career has been focused on developing a “smart” prosthetic hand. It’s potentially groundbreaking work in a fascinating field, but ultimately it matters not a jot unless it can improve the quality of life for amputees.

“Growing up, my grandmother taught me a whakatauki, ‘he aha te mea nui o te ao?’ or ‘what is the most important thing in this world?’ I saw by the way that she acted that people were the most important thing,” says Mahonri (Ngāti Hine and Ngāti Tuwharetoa). He also points to a seminal experience he had while on mission in South Africa when he met a young mother who had suddenly lost the ability to walk. He was 19 at the time.

“I thought that whatever I was going to do with my life, it had to involve helping people.”

After returning from South Africa, Mahonri finished his engineering undergraduate degree, then pursued doctorate research into a brain-controlled prosthetic hand.

It’s a fast-developing field, with efforts increasingly focused on muscle-machine interfaces, autonomous robotics and vision.

“We’ve come up with about five or six different ways you can control these prosthetic devices with different body signals. One of the main ones is EMG, or getting signals from the muscles, which is quicker and more accurate than trying to do that from the brain,” he says, adding that for all the technical interest and challenge, he never loses sight of the ultimate goal.

“When you talk about amputees it’s never just the physical loss they’ve experienced. It’s social, it’s mental, it’s spiritual, it affects their family. So, you’re not just trying to restore a limb; you’re trying to restore a bit of all those other aspects of life as well.”

Dr Mahonri Owen, Senior Lecturer at the University of Waikato’s School of Engineering. Photo: Royal Society Te Apārangi

Leading Māori into STEM

Mahonri’s other huge passion is encouraging young Māori into science, technology, engineering and maths (STEM) careers. Previously, he worked for Palmerston North-based Pūhoro STEMM Academy, which was launched in 2016 to help address low engagement by Māori in STEM-related career pathways.

“I feel like I’ve grown up at the interface of Te Ao Māori and STEM, so it’s personal. I also feel I’m only where I am thanks to the opportunities that I’ve been given by good people. So, my view is that if I’m in a position to help support Māori coming into the STEM space, and specifically engineering, then it’s my duty to open doors for them,” he says. “I joke that although I’m at the University now, I’m still working for the academy. I love being able to get out to high schools to support those kids. The benefit now is that I can say, ‘If you’re studying engineering, come and see me and I can look after you.’”

Fronting the media

Engineers are an important voice in the media, providing expert commentary on issues of the day. Here are some top tips from from Communications Manager at Te Ao Rangahau, Lachlan McKenzie, for when a reporter calls.

Have a plan

News doesn’t wait, so take the call or respond as soon as you can. Ask about the reporter’s angle, deadline, and who else they’re speaking to. If you feel you can comment, arrange an interview.

Key messages

Memorise the three things you want your audience to know and keep returning to these, no matter what you’re asked.

Sound bites

Aim to express your key messages as a simple phrase, like “Drop, cover and hold” “Stay home, save lives.”

Keep it simple

Know your audience. While you’ll be providing expert commentary, your audience might know nothing about your subject. Explain what has happened and why, what it means for them, and what to do. Speak slowly and clearly. Use easy words and avoid jargon.