10 Oct 2024

From building transistor radios as a child in the 1950s to becoming a global leader in computational physiology is quite a journey. But that’s the path newly-Knighted Sir Peter Hunter HonFEngNZ has taken as he’s helped put Aotearoa on the map through bioengineering.

Recently appointed a Knight Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit for services to medical science, Sir Peter Hunter HonFEngNZ has always been a problem solver. He’s the Founder of the Auckland Bioengineering Institute (ABI) at the University of Auckland, and a founding member and Co-Chair of the International Physiome Project, which aims to build sophisticated models of human organs by integrating mathematics and physics with human biology. This will ultimately result in a complete virtual physiological human and could eventually revolutionise patient-specific diagnosis and treatment.

Sir Peter grew up in an engineering-dominated family. His father, an electrical engineer, was commissioned by the Broadcasting Commission to build New Zealand’s first closed circuit television, which he did in his garden shed with a young Sir Peter looking on.

“My brothers and I had our own workbench and tools in our bedroom. In those days you spent your childhood building things, pulling things apart and putting them back together.”

Sir Peter completed an engineering degree in Theoretical and Applied Mechanics at the University of Auckland in 1971, followed by a Master of Engineering focused on solving the equations of arterial blood flow.

“When I finished my undergrad degree, an inspirational lecturer, Mike O'Sullivan senior, offered a topic in blood flow, how to understand it using a mathematical approach,” he says.

“I’d done no biology at school, knew nothing about it,” he says. “But that opened the door. I just thought it was so interesting and that there were so many opportunities applying engineering and mathematical approaches to biology, that I never wanted to do anything else from that moment on.”

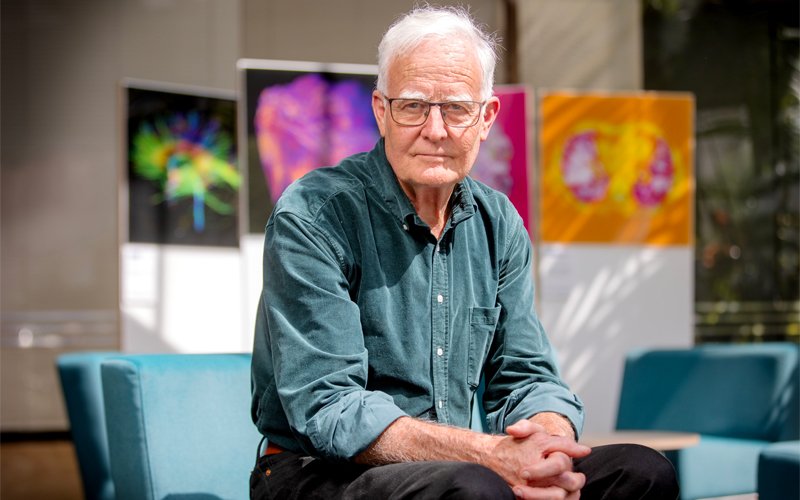

Photo: University of Auckland

Following his master’s degree, he was granted a Commonwealth Scholarship at the University of Oxford in England.

“I decided I wanted to jump in boots and all and did my PhD in the physiology department.”

He joined a group intent on building a model of the heart using very simplistic methods.

“That’s when I really began to delve into how you could understand heart anatomy using mathematical techniques to build models.”

He adds: “I was, in a sense, taking a punt on computing power increasing. And it did, thank goodness.”

Since then, Sir Peter’s vision of a digital model of the heart has grown into a programme called The 12 Labours, which aims to map 12 organ systems. The project is led by the ABI in collaboration with numerous international partners.

Where did such foresight stem from?

“Naivety. I didn’t know what I didn’t know,” he says simply.

“Everything is based on the laws of physics. That’s the case right across all areas of human endeavour, except for, at that stage, biology. It was felt that biology was just too complex. But biology has to satisfy the laws of physics as well and bioengineering brings that framework, that ability to use maths, physics and engineering to bear on physiology, anatomy and biology.”

While it’s still early days, he says bioengineering is going to play a key part in understanding the complexity of health and medicine, “... particularly as we get more measurements on a given individual, such a genes, blood biomarkers, whole-body physiological testing”.

My brothers and I had our own workbench and tools in our bedroom.

While working on this ambitious project, the ABI has spun out approximately 25 companies in the past 15 years.

“You can’t ask for public money to fund a very long-term goal without delivering in the interim. You need the long-term goal but also the capacity to spin out opportunities for application and employment along the way.”

Peter says medical technology, or medtech, has got huge potential to create both economic opportunities for Aotearoa and positive healthcare outcomes.

“New Zealand is a very good place to be trialling new approaches to healthcare – we’re a small, well-connected, well-educated population with electronic health records.”

Peter says there’s a huge focus on health equity within the ABI.

“It’s about trying to move healthcare into the home environment. It’s a long-term solution to keep people out of hospitals and reduce the cost of healthcare.”

Throughout his career Peter has received a cornucopia of national and international accolades and awards, but says the most significant was becoming a Fellow of the Royal Society (United Kingdom), which recognises many of the world’s most eminent scientists. The second, he says, is the Rutherford Medal, New Zealand’s most prestigious science award.

He sees his most lasting legacy in the establishment of the ABI, “... building a collegial working environment that has critical mass and is very strongly internationally connected. It has over 120 PhD students and shows that New Zealand can be an international player in science”.

What advice does such a high-achieving scientist give to engineers starting out?

“While you have to delve deeply to make a contribution in your field, it’s really important to be reading across a broad area, not only in science, but outside of it.” He adds: “In my career, I was probably pretty naive in a number of areas, but the more you read and delve into new areas, the more opportunities open up.”

This article was first published in the September 2024 issue of EG magazine.