2 Dec 2020

With the 10th anniversary of the September 2010 Canterbury earthquake gone, and the equivalent milestone for the 22 February 2011 disaster fast approaching, there’s likely to be plenty of reflection, including among engineers. So, what are some of the biggest professional – and personal – lessons learned?

When Holmes Group CEO John Hare FEngNZ CPEng IntPE(NZ) looks at Christchurch’s evolving post-earthquake cityscape, he sees something missing. It’s not the heritage-sized hole left by much-loved historic buildings – although they are sorely missed. No, what John’s engineer’s eye sees is a positive absence, evidence that a critical lesson of the quakes has been absorbed in the rebuild. There are few ductile concrete moment resisting frames, and – you’d hope – fewer precast concrete floors in the city’s new buildings.

“That was once all we used to do,” says John, who spent two years as principal engineering advisor to the Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Authority (CERA).

“You’ll hardly see any of those as new construction in this part of the world now – and that’s a good thing.”

So how have engineering practices changed over the past decade? How well have we adapted to the seismic challenge? And beyond buildings and infrastructure, what lessons have engineers taken from the human impact?

Johns says one surprise of the 6.2 magnitude quake was the havoc it wrought with some modern buildings.

“The real horror story of both the Christchurch earthquake and the Kaikōura event has been the level of damage to precast concrete flooring systems, which have been commonly used in New Zealand for a long time,” he says.

“Some of the older buildings actually performed better than might have been expected because they had more robust in-situ floor systems.”

Justice and Emergency Services Precinct. Image: Dennis Radermacher

People are choosing systems that are less likely to be damaged and more easily repairable. There are now quite a lot of base-isolated buildings being constructed.

That particular lesson has still not been taken on board, he says. Attention is being paid to alternatives commonly used overseas such as post-tensioned concrete flooring, but there’s resistance in the industry. Sure, precast concrete systems are cheap and widely available, he concedes.

“But, frankly, their ongoing use is questionable unless we find considerably different ways of dealing with them.”

Looking more broadly, however, he does see changes for the better. Floors in commercial buildings of any scale are now more commonly steel composite systems – or even timber in some cases.

“And people now are a lot more conscious of looking at seismic form, seismic structure – almost to the point where developers and tenants want the bracing on show so you can see that it’s safe.”

The sheer number of structures condemned after the earthquakes has also changed thinking about building resilience.

“People are choosing systems that are less likely to be damaged and more easily repairable. There are now quite a lot of base-isolated buildings being constructed.

“Previously, there were just a handful and they tended to be very specialised buildings – hospitals, Te Papa, seismic retrofits of important heritage structures – whereas now it’s seen a little more as something you might build into more routine buildings.”

However, he cautions that the use of new technologies doesn’t necessarily mean we can relax. One of Christchurch’s biggest lessons – an old one, but it was rammed home by the earthquake – was of the importance of keeping things simple.

“The more complicated your systems are, the more likely you are to get failures,” he says.

“With low damage design, a lot of people immediately think ‘high-tech’, ‘base isolation’, ‘viscous dampers’, and that sort of thing. But actually, if you do a bad design and put that technology into it, it will still be a bad design.

“The key is thinking not just about technology, but how we can keep things simple and regular.”

Changes from the ground up

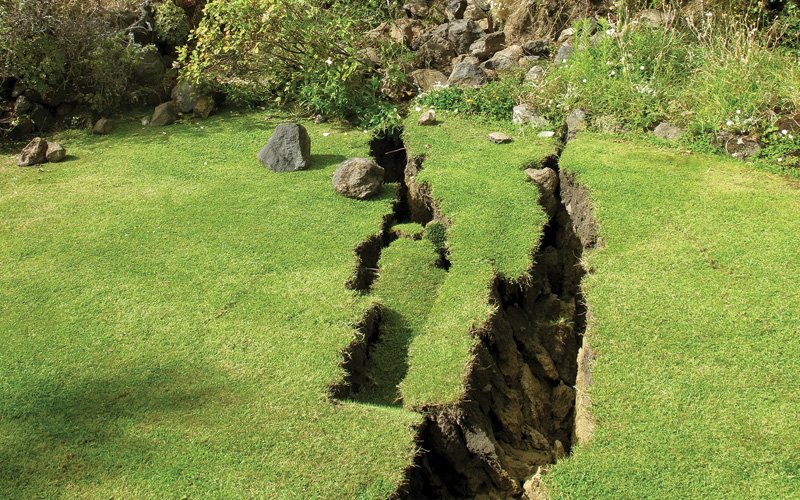

There’s also the question of the ground on which we build. More than 400,000 tonnes of silt came to the surface during the two earthquakes as a result of liquefaction, and swathes of Christchurch were rendered uninhabitable.

Veteran geotechnical engineer Dr Jan Kupec CMEngNZ CPEng IntPE(NZ), who leads Aurecon’s ground engineering team in the city, says that aspect of the disaster was a shock.

“In Christchurch, everyone – at least in the industry – appreciated there was a liquefaction hazard; it was always evaluated on a property-by-property basis. But no one thoroughly understood what it would look like if a large earthquake hit. That lesson has been learned. The industry and regulatory bodies now appreciate much more the impact on society from a natural hazard.”

He adds: “We have changed how we develop land, and what land we want to develop. We’re better at assessing the strength of the ground and its ability to respond to earthquakes, and we have improved foundation design significantly.”

This heightened appreciation of risk goes beyond earthquakes.

“It relates also to hazards such as climate change. We now appreciate that if you place a residential development near the seashore, for example, then you need to account for all the hazards associated with that.”

Land scar in Clifton. Image: Jan Kupec

The impact on people

What of the human side of the earthquakes? What did Christchurch teach the engineering profession in that regard?

Engineer Rob Kerr CMEngNZ CPEng IntPE(NZ) has had plenty of opportunities to ponder the question.

He was brought in to run Waimakariri District Council’s infrastructure recovery following the first quake.

He later spent time as general manager of the red zone and led a number of anchor projects, as well as the planning for the redevelopment of the Ōtākaro Avon River Corridor.

Rob says he came to understand “The Rebuild” as being a distinct thing from “The Recovery”. The former is a tool to deliver the latter, which is all about moving on from uncertainty and anxiety.

He cites a couple of anchor projects. The Margaret Mahy Playground involved a lot of “very interesting” engineering, but its significance was really as a “beacon of what Christchurch could be like”. Similarly, early public consultation over reconstructing a particular area of Kaiapoi might, on the face of it, have been about carriageways and footpaths, but actually it was more about engaging people in thinking positively about the future.

“This is where I think our profession sometimes lets itself down by failing to recognise the purpose of what we’re doing,” he says.

“The purpose of fixing a sewer is not to fix the sewer, but to enable the community to do a, b, c and d. So, the way we do things is really important.”

Christchurch exposed weaknesses in that regard.

It’s vital that when we provide leadership, that not only are we trustworthy and credible, but that we tell the hard truths as well.

“Sometimes, we engineers might know things, but we are really bad at explaining them. We also suffer from optimism bias. Too many times in Christchurch things were over-promised, and when they failed to materialise, it generated distress and distrust – and remember that we were in a context where there’d been some failures of engineering.”

Rob says: “It’s vital that when we provide leadership, that not only are we trustworthy and credible, but that we tell the hard truths as well.”

Expertise, credibility and communication are key. Rob agrees not every engineer will have all three.

“It’s really important that those who can communicate and who do have engineering expertise step up and lead.”“This is where I think our profession sometimes lets itself down by failing to recognise the purpose of what we’re doing,” he says.

“The purpose of fixing a sewer is not to fix the sewer, but to enable the community to do a, b, c and d. So, the way we do things is really important.”

Christchurch exposed weaknesses in that regard.

“Sometimes, we engineers might know things, but we are really bad at explaining them. We also suffer from optimism bias. Too many times in Christchurch things were over-promised, and when they failed to materialise, it generated distress and distrust – and remember that we were in a context where there’d been some failures of engineering.”

Rob says: “It’s vital that when we provide leadership, that not only are we trustworthy and credible, but that we tell the hard truths as well.”

Expertise, credibility and communication are key. Rob agrees not every engineer will have all three.

“It’s really important that those who can communicate and who do have engineering expertise step up and lead.”

Eddy Snook, photographed in Krakow, Poland. Image: Wioletta Kawulak

The impact on mental health

Of course, in Christchurch engineers were also among those affected by the trauma and stress of the disaster. The team at structural engineers Ruamoko Solutions, for instance, had barely moved into their new office on the corner of Manchester and Worcester Streets when the February quake hit. They watched buildings collapse, and within hours were thrust into the Civil Defence effort. For the next fortnight, a team of eight operated out of Managing Director Julian Ramsay’s CMEngNZ CPEng IntPE(NZ) lounge.

“We were running on fumes,” says Julian.

“And that remained the case for the couple of years, workload through the roof, trying to do our bit for the city.”

He saw the same pattern repeated among other engineers.

“You were highly sought after as an engineer following the quake, and tried to do everything you could, but it was to the detriment of a lot of people’s mental health – and I think the effects of that are still being felt.”

It’s important to face up to these things, to recognise the signs early, those changes in behaviour, and for the person affected to realise there’s no shame or stigma about having certain feelings.

For retired structural engineer John Snook CMEngNZ, the mental toll of the earthquakes cut too close to home. John and his wife Linley lost their 33-year-old engineer son Edward to suicide three years after the second quake. A thoughtful, adventurous and happy man, “Eddy” was unmoored by the February event, becoming increasingly anxious and obsessed with safety. His work with a local engineering firm was affected; a return to London, where he’d previously been employed, ended with his father having to bring him home.

John believes there’s been progress in New Zealand since then in talking about mental illness. But in 2011, communication wasn’t as open or effective.

“It’s important to face up to these things, to recognise the signs early, those changes in behaviour, and for the person affected to realise there’s no shame or stigma about having certain feelings,” he says.

“We need to treat mental illness like any other form of unwellness. Don’t hide it away; keep your self-esteem; and know you can get better.”

That message also goes out to employers in his profession.

“Engineers have a stressful life anyway, and I think it’s important for employers to make facilities available for the wellness of their staff – and, again, to communicate, and give people time out if they need it. These are things we feel strongly about as a family.”

There will be many other families reflecting on absences around the table when 22 February rolls around. We acknowledge their grief. And it’s likely that engineers and others in the construction industry will be prompted to think about what more could be done to make our built environment safer. But the 10th anniversary won’t be without an upside for some.

“I’m looking at it positively,” says Julian Ramsay.

“There’s more resiliency in our buildings, and some amazing new ones have been built – Tūranga, the new convention centre and the justice precinct are impressive in anyone’s eyes. I regularly reflect on the time I walked down the city mall on February 22 and think ‘wow, we’ve come a long way’.”

Find out more about Engineering New Zealand's range of wellbeing resources

This article originally appeared in the December 2020 issue of EG magazine