11 Mar 2025

It’s five years since the Covid-19 pandemic hit our shores, forcing industries and sectors – including education – to find a “new normal”. Though it was undoubtedly a devastating period, it spurred alternative and even novel ways of educating engineers. So, what worked well, what has been embraced and expanded, and what is best left in the past?

The onset of the pandemic saw both engineering faculty and students at the University of Auckland forced to adapt to an asynchronous style of learning. Students accessed prerecorded lectures, followed by drop-in sessions. Labs and design courses, which typically require a more hands-on approach, were replaced with virtual modelling and simulations. Final year projects moved to online formats.

“Some students really struggled, and we saw more cases of students requiring pastoral support,” says Dean of Engineering Richard Clarke MEngNZ.

“We found that the lack of scheduled lectures created problems for student learning and a drop in the level of student engagement.”

Richard Clarke MEngNZ.

The same was true at the University of Waikato.

“The experience we had with online teaching was quite negative,” says Dean of Engineering Dr Mike Duke MEngNZ.

“We looked at it as a low-grade alternative that got us through a difficult period.”

Despite these challenges, Richard notes that the calibre of engineering graduates remained unchanged.

“We still maintained our standard. We still made sure they were meeting the learning outcomes – albeit through these different methods. What it did mean is that we had to provide more wraparound support for those students to make sure they could succeed.”

Dianne Arnold, People and Culture Manager at engineering consultancy firm BCD Group, can attest that “… the recent cohort of graduate engineers have the required technical knowledge expected of a graduate”.

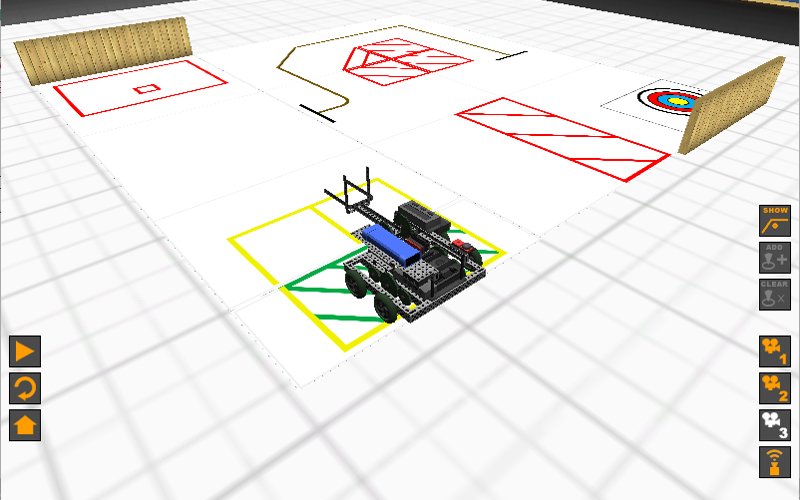

Virtual simulation environments often replaced hands-on robotics labs during lockdowns. Image: University of Auckland

Bridging the gaps

While the pandemic forced students to adjust to remote learning, it also equipped them with technological adeptness.

“Our graduates coming through seem to get on board a lot quicker with any technology changes. They’ll be making suggestions or teaching some of our more experienced employees about software shortcuts,” says Dianne.

“Organisations need to harness what their grads bring to the table. As tech natives, how they utilise software can allow an organisation to become more efficient.”

Yet, reduced in-person learning and face-to-face interactions also have their drawbacks. Mike noticed that students lost the teamwork benefits of being on campus.

“We’re trying to develop two sets of skills. There’s the engineering side – the technical skills of designing, building, assembling. There’s also the professional skills of working in teams – how to manage a project, delegate work, deal with conflict resolution to achieve an objective. If you’re not doing that as an engineer, you’re missing out on so many things.”

Dianne Arnold. Photo: BCD Group

We’re having to work harder to close the gap in terms of soft skills and communication with clients.

To mitigate this loss in team-building skills, the University of Waikato’s engineering faculty ran additional sessions for students.

“We were running extra workshops so they could catch up with the skills they were lacking,” Mike says. “It wasn’t perfect, but it was the best thing we did.”

Similarly, part of the feedback Richard has heard about the recent cohort of graduates is that “… some of the soft skills, social skills, and confidence are not necessarily there because they’ve spent some of their years with no contact with their peers, and that’s where the impact has been greatest”.

Dianne echoes this sentiment: “We’re having to work harder to close the gap in terms of soft skills and communication with clients.”

To achieve that, BCD Group’s graduate programme involves a buddy system where graduate engineers are allocated a buddy to work alongside them and help them grow and develop. The programme also includes training sessions and workshops on topics like communication, critical thinking, connectedness, and even project management and client management.

“It’s important to introduce the career pathways early,” Dianne says. “You show up as part of a grad programme, but we treat you as an individual. If you’re motivated to pursue a specific pathway, we’re going to support you.”

Catalyst for change

While education has now returned to the pre-pandemic norms of in-person learning, Covid-19 sparked shifts in the way Aotearoa is educating its next generation of engineers.

“It accelerated something that was happening a bit before Covid, which is more of an on-demand culture,” Richard says. He has observed, for instance, that students prefer individual appointments at a time that suits them rather than come to fixed office hours. Students also expect teaching staff to be available on virtual forums and discussion platforms to answer questions about classes as they arise.

“Previously, you would make yourself available during office hours, and then students would understand that they had to rely on self-learning outside of those office hours. With Covid, it accelerated that expectation of flexible learning and flexible access to support from teaching staff,” adds Richard.

At the University of Waikato, flexible learning happens in the form of recorded lectures.

“We realise that people live busy lives, and some students have part-time jobs so they can watch the lectures if they can’t attend. But a lot of activities in our degree programme require you to be on campus if you’re going to pass,” Mike says.

This notion of flexibility has extended to the workplace.

“Because the learning is happening in such a flexible model, the expectation is that when they come into the workforce, it is flexible. I think the crucial thing with graduates is actually immersing themselves in an organisation and deeply understanding how they can use their technical knowledge to add value to society and the clients they’re working with,” Dianne says.

And while BCD Group offers some level of flexibility, Dianne notes that the firm wants its graduate engineers to be “… in the office surrounded by experts in your respective fields so you can learn your craft and learn how to apply the technical knowledge you’ve gained through university. Showing up and being present and surrounded by people is a positive for your own growth and development.”

BCD graduates and interns get out in the field, including for geotechnical training and site visits. Photos: BCD Group

Tech-forward tomorrow

Envisioning the future of engineering education, Richard believes technology will continue to be a significant enabler.

“If we are to move into this more on-demand, personalised learning, we need to do it well, and we need to invest in and put in place the infrastructure and resources so the production value and quality of the materials are comparable with other media that our students are engaging with in the teaching and learning space.”

Additionally, AI will play a huge part in advancing engineering education.

“The early work in this space was figuring out how we make sure we’re preserving academic integrity. We’re now moving toward more of a stance around how we can take advantage of this technology,” Richard says.

He cites the use of AI as a triaging tool, for instance, to help answer students’ straightforward questions and escalate more complex ones to a member of the teaching staff.

“This is an area where AI can help with the notion of personalised learning.”

No matter how technology evolves, the most vital element in how engineers are educated will remain: “It’s making sure we’re graduating engineers that have the core competencies and the engineering accreditation standards,” says Richard.

“The competencies will stay – it would just be how we meet those, given the tools that are available.” He adds that critical thinking, analysis and independent research are even more relevant now in the age of AI.

It accelerated something that was happening a bit before Covid, which is more of an on-demand culture.

For Dianne, the long-term outlook for engineering education goes beyond technical skills.

“We encourage current and future graduates to consider the future of the industry and envision the role of an engineer in the next decade, and consider what skills are important to develop. When designing environments and structures that should enhance people’s lives, we must remember that, ultimately, it’s about the people.”

While evolution is inevitable, the engineering education sector will remain resilient.

“The world is always changing. There will always be events like Covid or new technologies cropping up,” says Mike. “As engineers, we have to accept change and adapt to it.”

Next-level mastery

Taking a cue from the pandemic-era switch to online learning, the University of Canterbury is embracing flexible learning through its Tuihono UC Online courses and programmes. However, unlike the rushed online learning designed for emergencies, UC Online is purpose-built to create an engaging experience tailored to online learners. “The University of Canterbury has a strategy to make learning as accessible and flexible as possible. Putting more of our degrees online is integral to this so we can serve a larger audience, including working professionals,” says engineering management programme lead Lulu Barry. “The focus is on postgraduate study because learners don’t have time to take a year or two off to complete a master’s degree.”

While the university’s Master of Engineering Management degree has been in-person since its introduction in the early 2000s, the programme is moving to a fully online set-up this year to meet the growing demand from Aotearoa’s engineering and project management professionals who want more control over when and how they study.

Lulu says this is particularly good for mid-career engineers who can then work and study at the same time. We do have some early-career students also enrolling, which is good, because it shows that to become managers, they can’t just rely on what they learned as engineers, but they also need to acquire leadership and business skills.” In time, the University plans to offer a suite of master’s degrees.

This article was first published in the March 2025 issue of EG magazine.