10 Jan 2023

New Zealand’s housing story has been described as both tragedy and farce, but recently it may have tipped into something more like horror. However, some innovative, engineering-led developments might help pick up the pace of building new houses and go some way to addressing the housing crisis.

We’ve watched the affordability metrics head off a cliff; heard the stories of people living in their cars; lived through the skills shortage and the plasterboard crisis, and experienced Waiting for Godot-like interregnums between consenting and the first shovel hitting soil. News of a major slump in new house build enquiries doesn’t constitute a solution to the issues that plague the construction industry, from boom-and-bust cycles that discourage investing in technology and training, to lack of competition in the materials supply chain, to snail’s-pace consenting and apparently intractable customer demand for one-off bespoke dwellings.

The Government has attacked the problem with a raft of measures that include legislation to compel more intensive urban housing, an infrastructure acceleration fund, a plasterboard taskforce, and inventive approaches to the preconstruction phase by the likes of Kāinga Ora. But the fact remains that we continue to build homes pretty much as we did 50 years ago, using the same methods and trades, in a cottage industry dominated by “one-man-band” operators. Whatever happens at the front end, you can bet your house on a new home taking five to six months to build.

But some people are challenging those default industry settings with innovative, engineering-led alternatives that could help pick up the pace. Advocates for prefabricated solutions, for instance, finally have some wind in their sails. A handful of ventures offering at least partial prefabrication have arrived in the market, touting quicker, more efficient, and more affordable builds that also have baked-in sustainability advantages (less waste, for one thing). Admittedly, some are focused on servicing the upscale bach market, but not all of them.

Customising for customers

In September, a one-bedroom, two-bathroom worker's dwelling materialised on an orchard near Cromwell, Central Otago. Consisting of prefabricated components that arrived on site already clad and glazed, it went up in 13 hours, from bare foundations to a fully weathertight structure ready for fit-out. The building is a prototyping exercise by Flexi House, a Lower Hutt-based start-up that wants to bring a product approach to house building, based on repeatable, scalable components manufactured in a factory and shipped to site.

Flexi House, Mount Pisa. Image: Flexi House

Founder and CEO André Heller distinguishes Flexi House from both traditional “one-off” builders and more recent volumetric, modular-based, transportable ventures.

“We’re trying to create a system that delivers unique design outcomes that isn’t a small home solution, but something that is scalable to 200 or 300 square metres,” he says.

“Adopting a product approach means you break the house down into repeatable, standardised elements, and create a library of components that are interchangeable throughout the building.”

To build something of that size and volume without steel portals, you’d have a lot of engineers scratching their heads.

– André Heller

As the name suggests, the emphasis is on flexibility – “Your Flexi House is designed to grow with you”. In the case of the Cromwell dwelling, it will eventually be extended – seamlessly – into a four-bedroom home. There are no nails, no glue or plasterboard; rather the system is built around screws, bolts and plywood panels. Materials include shiplap timber cladding, laminated veneer lumber framing, a wool-polyester insulation and cork floors, with an emphasis on sustainable or renewable sources. Within the parameters of the standardised elements, customers can customise their home using an online tool that will one day include live pricing.

It’s flexible – and it’s quick. The prototype Central home was constructed in seven weeks by manufacturing partner Makers Fabrication in its Lower Hutt factory. André, whose background is in product design, says that will get faster as the company shifts into production runs, starting in 2023.

“It all comes down to process and repeatability. We’d be easily able to extract 20 or 30 percent out of the process by building just five or 10 houses. But we want to scale this nationwide across multiple factories, which creates significant manufacturing efficiencies. We’ll be able to cut 50 percent off each project based on those numbers.”

It’s still early days, of course. But Flexi House has already cracked a number of gnarly problems.

“This is a panelised build, and all the structure is effectively contained within those panels. Once they’re installed, it’s done – no trusses, no additional framing,” he says, adding that we’re talking here about a 6.5-metre-wide structure with a raked open cathedral ceiling.

“To build something of that size and volume without steel portals, you’d have a lot of engineers scratching their heads.”

The key, he says, was to engage the talents of Alistair Cattanach FEngNZ CPEng IntPE(NZ), the Dunning Thornton Director who, among other notable projects, led the structural engineering team responsible for Scion’s groundbreaking timber innovation hub in Rotorua, Te Whare Nui o Tuteata.

Next steps? Currently, Flexi House is trying to secure investment to build 15 or so homes to “nail down the system”, then hopes to partner with manufacturers and local builders around the country to go commercial.

Whatever happens, André reckons offsite manufacturing is the future. Not only is it faster and potentially cheaper, it delivers better performing homes for a lower carbon footprint.

“Delivering materials to site and building onsite is old technology. We need to be working towards offsite.”

The four Rs

At the University of Canterbury, a team of engineers is coming at the problem of pace from another angle.

Led by earthquake engineering expert Professor Rajesh Dhakal CPEng IntPE(NZ) the project aims to develop a novel building system that would speed up the delivery of concrete buildings by obviating the need for any onsite concreting for connecting beams, columns and floors.

Traditionally, says Rajesh, those connections have required preparing a watertight framework, followed by an onsite pour, followed by perhaps a fortnight of curing before work can proceed. By contrast, the Canterbury innovation – christened the Rapid, Reduced-carbon, Resilient and Recylable Modular Building System, or R4MBS for short – involves standardised prefabricated concrete modules that are yoked together using novel, low-damage, detachable steel connections. It’s all steel plates, bolts and holes, a system that not only theoretically allows for quicker construction – the “Rapid” part of the formula – but also reduces the amount of resources and waste involved.

Should it pan out, Rajesh stresses its game-changing implications.

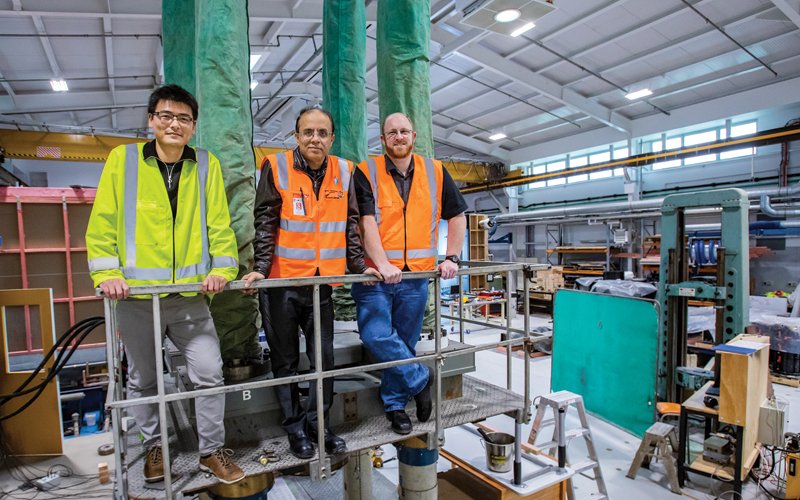

From left, Dr Brian Guo MEngNZ, Engineering Professor Rajesh Dhakal CPEng IntPE(NZ) and Professor Geoff Rodgers. Image: University of Canterbury

“We use the word ‘monolithic’ for how we currently build. Although the components are modular, after we build they all become one integrated unit. Whereas with this system, we want to keep that modularity intact. You don’t need that extra concrete; all you need are the concrete components, the beams and columns, and standardised holes to take bolts at certain locations. Then you put in the steel plates and tighten.”

There are other potential benefits to R4MBS, including seismic performance – the “Resilient” part. Hit by a severe earthquake, damaged connections could be repaired or replaced to quickly restore the building. And rather than having to demolish a building at the end of its life, its elements could be recycled – a major win for its lifecycle carbon footprint.

“This will be the first building system in the world where we have gathered together the different features of prefabricated modular building construction and low-damage seismic technologies to come up with something so potentially impactful.”

That’s the theory, at least. Again, there’s plenty of water to flow under the bridge, with proof-of-concept lab testing the next step, according to Rajesh, who adds that the system is ideally geared to mid-rise buildings – including for medium density housing.

Rajesh’s team has homed in on one element of the ponderously paced and costly nature of building in this country. But that larger problem is going to have to be tackled from a variety of angles – including addressing the supply of critical building materials. This year’s plasterboard shortage, albeit Covid-19-related, highlighted longstanding issues, not least how difficult it can be to get alternative products into the pipeline.

Board at home?

One recently launched innovation to have successfully navigated the plasterboard compliance pathway is saveBOARD. Its Te Rapa factory upcycles everyday packaging waste such as construction soft plastics and liquid paperboard into construction boards, as well as internal linings and rigid air barriers – essentially, they turn your coffee cup into wall lining. It’s an exemplar of closed-loop, low-carbon footprint thinking, but it also may have a small role to play in speeding up builds.

Co-founder Paul Charteris CMEngNZ says they haven’t revolutionised how a board is used. But saveBOARD does have the benefit of exceptional bracing and impact performance, which opens up more options for how you build – he cites using Structural Insulated Panels or panelisation of the building envelope without the need for nogs or dwangs.

“Ultimately, the best use of our boards is in any type of prefabricated factory-build system where you can put a rigid air barrier along with bracing elements in place without worrying about transport damage to plasterboard, so that when you stand up the building envelope it’s ready to go.”

saveBOARD turns everyday packaging waste into construction boards. Images: saveBOARD

This article was first published in the December 2022 issue of EG. The full version of EG is available in your member area.