10 Jun 2019

Want to feel fuller sooner, taste saltier salt or better chocolate? Engineers can help.

Like Isaac Newton in the famous origin story, University of Auckland Professor Bryony James FEngNZ can thank an apple for altering the trajectory of her career. The Deputy Dean of the Faculty of Engineering trained as a materials engineer in her native United Kingdom, and was happily running Auckland’s Research Centre for Surface and Material Science when she had her version of Newton’s Lincolnshire garden moment. Working late one evening, on a whim she put a piece of apple under an electron microscope. The following day she mentioned what she’d seen on the slide to a food science lecturer, who began explaining some of the properties of apples.

Professor Bryony James FEngNZ and Dr Colin Doyle in the lab at the University of Auckland’s Research Centre for Surface and Materials Science. Photo: Geniesa Tay/ University of Auckland

“She talked about the properties of food in the same way that I would have spoken about the properties of a piece of metal,” says Bryony, who was named as an Engineering New Zealand Fellow earlier this year.

“It seemed an interesting avenue to pursue.”

Today, she describes herself as a materials engineer who has “strayed from the true path” of metals, plastics and ceramics to study food – particularly, the impact of food structure on food properties and oral processing. If that sounds ivory towerish, it shouldn’t. Her ongoing research into food texture and its impact on satiation – feeling fuller, sooner – potentially opens up a whole new area of product development for New Zealand food manufacturers. And it could furnish part of the answer to the obesity epidemic. Other work has proved useful to the wine and dairy industries.

Bryony’s career switch is part of a larger story about the growing role of engineers and engineering in what we eat and how it is produced. Take rising Auckland-based venture Sunfed Foods, for example, whose plant-based “Chicken Free Chicken” reportedly packs double the protein of chicken. Founder Shama Lee has described Sunfed as a “product-led engineering company”. Or consider Massey University spinout BioLumic, that has developed UV light technology that in some instances has improved the yield of crops by nearly 40 percent. In these innovative New Zealand food ventures, engineers are working hand-in-glove with scientists and food technologists to create new products and better processes.

Finding the sweet spot

If there’s an overarching mission here “it’s about helping New Zealand to make more money out of its biological resource,” says Professor Richard Archer FEngNZ of Massey University’s School of Food and Advanced Technology.

“That can be by adding value to consumer products, through reduction of waste and, increasingly, by shifting to renewable resources. The absolute sweet spot for New Zealand involves the application of new high-tech means – robots and AI and sensors and so on – to the production and processing of food. And engineers are right in there.”

In Bryony’s case, her research is closely informed by her materials engineering background.

“How do you use engineering to create the structure in the food that will give you certain properties when you eat it? For the most part, I’m interested just in the chewing part.”

Her structural analysis expertise was tapped for the $170 million Primary Growth Partnership programme, aimed at transforming New Zealand’s dairy value chain. Among other things, she helped Fonterra to hone its process to produce mozzarella-style cheese.

We build machines that travel up and down a greenhouse applying the light recipe to the seedlings.

“It sounds like such a minor thing, but mozzarella exports are absolutely huge,” Bryony says.

The work on texture and satiation is potentially more significant. Previously, the only supposed link was that high-textured foods tend to take longer to chew, which contributes to feeling fuller sooner.

“What I wanted to answer was: is there an effect of texture that’s independent of oral transit time?” says Bryony, whose world-first study demonstrated that satiation is indeed enhanced when people eat texturally complex food.

In collaboration with a psychophysicist and a neuroimaging expert, she has secured a Marsden Fund grant to investigate further.

“The next big question is, why? If we could understand that, then food manufacturers could make use of it to produce and market foods that enhance satiation – snack bars, for example, that leave you feeling fuller sooner – by manipulating people’s chewing behaviour. There are opportunities there, too, for developing food products that go beyond where we are now to achieve particular nutritional outcomes.”

Bryony believes engineers will be important players in two other major food trends: personalised nutrition, and traceability. In the latter case, she says, “New Zealand has a big provenance story to tell, and engineers can provide the evidence in terms of remote sensing, handling big data, and so on.”

Shining light on the situation

At BioLumic, the application of cutting-edge technologies is very much focused at the other end of the food chain – growing crops. The Palmerston North-based biotech firm offers growers tailored UV light “recipes” to activate natural mechanisms in seeds and seedlings that increase plant growth, vigour and natural defence mechanisms, resulting in increased yields at harvest.

“Our engineering team is where the rubber meets the road,” says BioLumic Senior Engineer Jason Phillips MEngNZ.

“Once the scientists have developed a UV recipe, it’s up to the engineers to deploy it in a tangible, commercial way. We build machines that travel up and down a greenhouse applying the light recipe to the seedlings.”

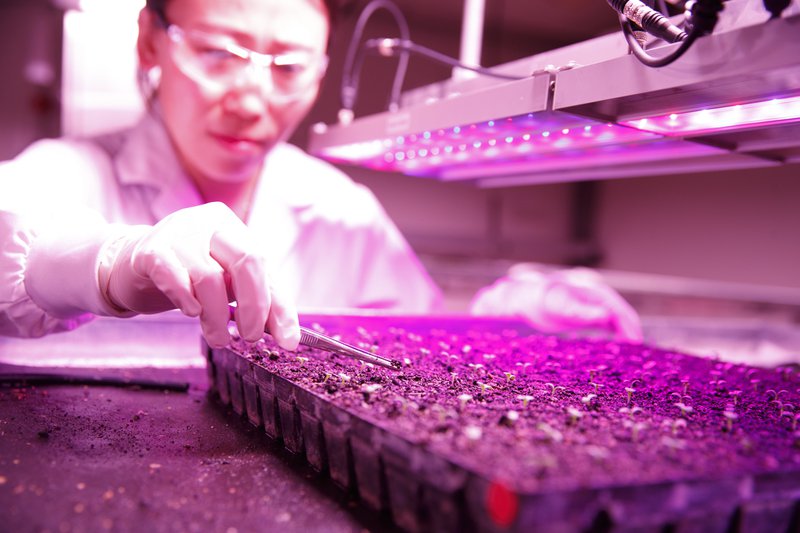

BioLumic Senior R&D Scientist Dr Lulu He assesses the effects of UV treatment on young seedlings. Image: BioLumic

Jason says there’s also an automation element – a control system that means wherever you are in the world, you can remotely check in on a machine’s status and adjust any operating parameters.

“That’s all pretty traditional engineering – designing a machine and automating it. But the excitement for me going forward is incorporating the Internet of Things and computer vision and machine learning.

Biolumic is evolving a technology solution in which a machine can take environmental data from its surroundings and data on the specific plants being treated, run that through an algorithm and have it dynamically adjust how the machinery deploys a UV treatment in real time to optimise development for those plants.

“That’s groundbreaking stuff from an engineering perspective.”

Where there’s smoke…

Elsewhere in New Zealand, engineering smarts are being deployed to bring ancient food processes onto a modern footing.

Richard Archer highlights work being done at Massey on culinary smoking, a technique that has been used for centuries to preserve food. The problem is that commercial smoking involves polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), which are carcinogenic.

“It is, however, possible to make smoke from wood that has no PAHs,” says Richard, who serves as Chief Technologist for the MBIE-funded Food Industry Enabling Technologies research and development programme.

“The challenge is, how do you engineer that on a realistic scale, so that every piece of wood is exactly the right temperature all the time? The research will end up resulting in a fairly simple device, because we always try to get back to a simple execution of complex principles.”

Salt of the earth

In a nutshell, that’s what engineers contribute to innovation in the food industry – practical solutions.

“Engineers are central to the whole argument about food innovation, and critical to obtaining functionality in the final product,” says Professor Timothy Langrish of the University of Sydney’s School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, who has a particular interest in improving nutrition.

Among other projects, the expat New Zealander has investigated ways to make salt “saltier”, maximising taste while reducing sodium intake, and is collaborating with medical researchers at the University of Sydney on developing foods that could help to reduce cancer recurrence.

“Where engineering comes in is making sure we do it in a way that’s functionally effective, but also cost-effective,” he says.

This story originally appeared in EG magazine. To subscribe to EG, email hello@engineeringnz.org.