21 Mar 2025

Be it buildings, energy or transport projects, keeping low-carbon design in focus from the outset is making a difference.

In the face of a climate crisis, the goal of designing buildings for low-carbon outcomes is urgent. But a bit like the proverbial oil tanker, the construction industry is notoriously slow to turn, and in any case, who’s going to start the revolution?

In fact, according to the Heavy Engineering Research Association (HERA), radical change is not required. “Achieving our national carbon reduction targets in the built environment is not just possible, it’s within our grasp,” writes HERA CEO Dr Troy Coyle in the foreword to a new HERA-led study, “Circular Design for a Changing Environment”. She adds, “With the right design choices, carbon emissions can be cut by more than 50 percent – starting today.”

HERA CEO Dr Troy Coyle. Photo: Tim Hamilton/Visionworks Photography

The benefits of clever design

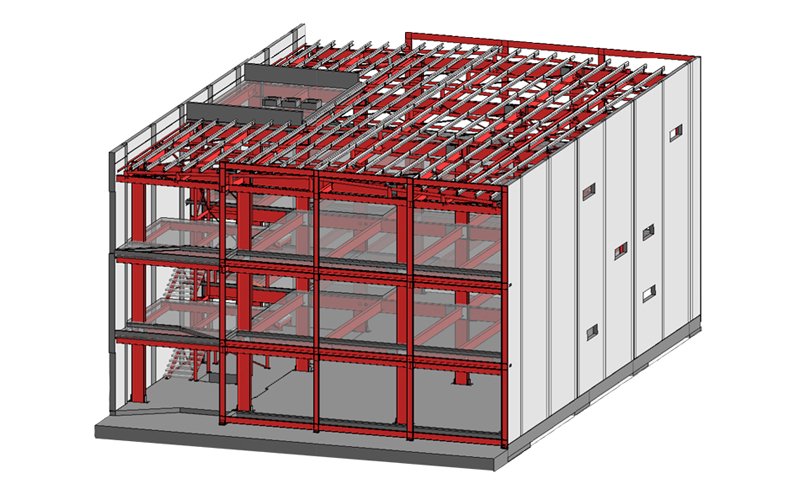

It’s a bold call, but it’s supported by the evidence. The HERA study employed a Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) analysis to gauge the emissions impact of a range of different construction materials and design approaches on six low-rise buildings. For their baseline, the researchers selected a 2014 Christchurch office building that had been constructed with a conventional steel-concrete composite flooring system and a seismic system involving concrete shear walls and steel moment resisting frames. (It was chosen because its cradle-to-cradle embodied emissions were the closest to average from among the six.) Against this reference building, they explored three variations of materials – low-carbon steel, low-carbon concrete and a combination – plus three design alternatives, including replacing the steel frames with reinforced concrete frames, replacing with them low-carbon concrete, and switching the flooring system for a steel-timber hybrid.

The takeaways? Clever design can significantly cut carbon, with steel, timber and concrete all having a role to play.

A low-rise office building was used as a case study for HERA’s low-carbon design research. Photo: Aurecon

“Our case study showed a reduction of 57 percent was achieved using our low-carbon and circular design hierarchy,” says Troy, who notes that the various design and specification choices involved in the study are all readily available in Aotearoa today, including low-carbon steel and concrete.

HERA’s next step will be to develop practical guidance for designers, specifiers, engineers and other practitioners with an interest in low-carbon and circular design, initially with a focus on low-rise buildings. The study itself will be made freely available on HERA’s website early in 2025, along with webinars to help with adoption.

Meantime, Troy offers some general observations on how we should be thinking about low-carbon design and circularity.

“There’s a focus on up-front carbon because we’re in a climate crisis, but we also need to make sure we design for a low-carbon future. Extending the life of a building has obvious carbon benefits, but ideally we should be designing for multiple lives and resilience also.”

Designing for longevity

Designing for disassembly, for instance, involves using reversible connections such as bolt studs rather than welded shear studs. Designing for longevity, meanwhile, will rely on innovations such as reusable low-damage moment resisting frames with optimised sliding hinge joints to enable the structure to withstand and recover from seismic events. As for materials, the focus should be on specifying low-carbon.

On that point, Troy warns that the HERA-led study found that some LCA tools don’t include the most up-to-date material options, including the low-carbon steel and concrete that’s already in use in this country.

“We’d advise engineers to familarise themselves with the latest Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) and low-carbon material options, because without that knowledge the use of LCA tools can lead to design choices that aren’t evidence-based.”

Her comment says something about the potential for getting things wrong when taking a low-carbon approach to building design. It’s complex, and even seemingly minor decisions tend to have carbon consequences.

Beca's Carbon Navigator, Phoebe Moses. Photo: Beca

“Any decision you make that means new materials are used or there’s a change in the amount or type of energy used to complete a function or a change in process, you impact carbon for better or worse,” remarks Phoebe Moses CMEngNZ CPEng.

Phoebe, a trained structural engineer, has spent the past couple of years operating as a “Carbon Navigator” for Beca. It’s a role that isn’t so much focused on internal practice changes, but on helping Beca’s clients and project teams reduce the emissions associated with building designs from the very start.

Buildings alone are responsible for around 20 percent of New Zealand’s emissions.

“I make sure people involved in a project have the information they need at any given time to make a carbon-informed decision. At the start of a project this will typically begin with me leading workshops… and I will stay closely involved through the early design stages, providing targeted analysis of options and feeding back to the team the carbon impacts of their design decisions. “I also become more involved in the specification and procurement process, making sure that decisions made earlier are carried all the way through.”

Engineers have a key role to play, Phoebe says.

“Buildings alone are responsible for around 20 percent of New Zealand’s emissions. And when you consider all the other realms in which engineers have influence such as industrial processing, food and beverage, and waste management, that number increases to almost half of our total emissions. Obviously, engineers aren’t the only people in the room making decisions, and there are other factors at play (time, cost, quality). But that’s what makes a good engineer: someone who can optimise for all of these aspects. We’re just asking that people add one more lens to their decision-making.”

She cites a couple of recent examples of successful buildings where engineers were closely involved in achieving a low-carbon outcome.

“The first is AUT’s new Tukutuku building, which opened in July 2024. The architect and sustainable buildings engineer coordinated to design a super high-performing facade, designed to balance daylight and energy performance, and followed a passive-first approach, using building physics to minimise any mechanical interventions.

She says that the building services engineer and structural engineer collaborated to choose systems that were super-low embodied carbon and operational carbon, with a mass timber superstructure and raised floor with displacement ventilation.

“Another example is the University of Auckland B201 building, which opened in February 2024 and is a case of adaptive reuse. Hopefully most people are aware that this is one of the best ways to reduce carbon emissions from building activities.”

Phoebe continues: “It saved all of the carbon emissions that would have been needed to build a new structural frame. While reusing the building, the project team also replaced the facade with a new high-performance facade, changed the building systems to be all electric, and added solar panels on the roof to reduce operational energy and carbon.”

Having the energy to change

Of course, low-carbon design isn’t only applicable to buildings. The University of Waikato’s Ahuora Centre for Smart Energy Systems, for instance, is bringing the same thinking to bear on industrial process heat, which contributes 28 percent of New Zealand’s energy emissions and is a formidable decarbonisation challenge.

Working with companies trying to achieve net zero, the Ahuora team focuses on three areas, says Assistant Director Dr Tim Walmsley MEngNZ. “The first is looking at how you become more efficient in your factory – so process and energy efficiency. Then it’s how do you transition your energy production or utility systems to convert purchased fuels and electricity into the heating and cooling your system needs in an efficient way. Finally, it’s about provision of renewable energy, both fuels and electricity, and the strategic and timely generation of that energy.”

University of Auckland B201 building’s double-height atrium, enclosed by an innovative hybrid steel and glulam timber roof structure. Photos: Jasmax

The centre, which is partly funded by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment’s Advanced Energy Technology Platform and collaborates closely with the University of Auckland and Massey University, currently has 22 PhD students. (Master’s students and undergraduates are also involved.) Of the 130-odd projects so far, Tim highlights a recent one in which a student worked with a Christchurch biosciences company on the problem of a new heat pump interacting problematically with a chilling unit. To solve it, the student first created a dynamic model of the system, then developed advanced control features. He also picks out an ongoing project in Kinleith where a student is investigating how to lower energy demand at the Oji Fibre Solutions’ pulp and paper mill.

These aren’t just one-offs, Tim stresses.

“Our mission is to help New Zealand industry transition to net zero, following the lowest-cost pathway. So, we work with individual companies on very specific and complex problems that they’re facing, but then once the student is finished, we try to find ways to generalise what they’ve done. From there, we aim to develop software that semi-automatically or automatically addresses that same kind of problem elsewhere for a range of companies.”

AUT's Tukutuku building’s sawtooth facade effectively excludes the intense north and west sun. Photos: Jasmax

For that reason, after process and chemical engineers, the next biggest engineering discipline on the Ahuora team is software.

Tim says while the pathway for the team to make an impact on industry is through training, collaborations and the work of former students, it will also be achieved through software.

“We’re building a digital twin platform that companies will be able to use to model and optimise what they do in the factory.”

“Poop to Power” project

Kiwi engineers are working globally to decarbonise industry through low-carbon design. Take Chris Baddock CMEngNZ CPEng IntPE(NZ), for example. The Christchurch-based Electrical Discipline Leader for Stantec was Lead Process Control and Automation Designer on a recently completed cutting-edge bioenergy and thermal hydrolysis project for US water utility, WSSC Water. Quickly branded the “Poop to Power” project, the Piscataway Bioenergy Project treats wastewater and, rather than releasing the byproducts, captures them for beneficial reuse.

WSSC Piscataway Bionenergy Facility. Photo: PC Construction/Stantec

The project got its colloquial tag because it upgrades methane to Renewable Natural Gas (RNG), part of which is used on site as fuel for the plant’s combined heat and power generators, with the excess powering Montgomery County’s fleet of RNG public buses. “I detailed what equipment is required to monitor and control the process and how this equipment would function and operate,” says Chris, who became involved while working for Stantec in Vancouver, Canada, and continued his involvement remotely after transferring with his wife Alisha to Stantec New Zealand when the Covid-19 pandemic hit in 2020. They now work with a team of four to six New Zealand-based engineers on similar bioenergy projects in Kentucky, Virginia, Manitoba and Hawaii.

This article was first published in the March 2025 issue of EG magazine.