11 Aug 2023

The Ōtira Tunnel has been regarded as an engineering marvel ever since it opened on 4 August 1923, finally providing a rail link between Christchurch and the West Coast.

Cutting a straight line through the Southern Alps, the 8.5-kilometre-long rail tunnel was the longest in both the Southern Hemisphere and the British Empire in 1923. Since then, it’s provided a vital transportation link between the East and West coasts of the South Island, with around 70 trains still carrying passengers and freight through the tunnel each week.

The centenary event was hosted by Ōtira township with about 600 in attendance – roughly the population of the town at the peak of construction, compared to the few dozen residents of today. The town was originally built for tunnel workers and their families. A PA system had to be set up outside the small town hall where the official ceremony was held, so those who could not fit inside could still hear the speeches.

Speakers highlighted the many engineering challenges and triumphs involved in construction of the tunnel. Work started in 1908 and was expected to take five years at a cost of about £600,000, but was not completed until 15 years later, ultimately costing more than £1.1 million.

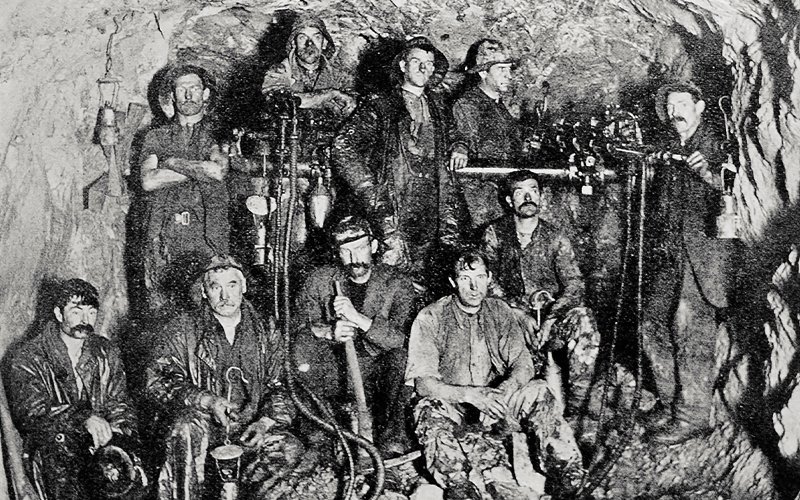

Tunnellers faced painstaking and dangerous work, using only picks, shovels, drills and dynamite to cut through the wet shale and rotten rock. Despite this, they achieved impressive precision, with line and level only out by a few centimetres across the tunnel’s entire length – in fact, the tunnel is so straight that light from the far portal can be seen from either end.

Tunnellers take a break from digging the Ōtira tunnel to pose for a photo in front of the rockface. Photo: Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections AWNS-19170927-36-6, photographer J Manson.

The original plan was for steam trains to traverse the tunnel but, over the course of its construction, electric railways became a viable option. Eliminating the potentially dangerous build-up of fumes within the tunnel was an attractive proposition, and a steam generating plant was built in Ōtira to power six electric locomotives along 14 kilometres of electrified line to pull trains through the tunnel.

In the 1990s the electrification system was dismantled in favour of a ventilation system, allowing diesel trains to travel through the tunnel unaided, and marking the end of electric rail in the South Island.

The tunnel was the brainchild of Public Works Department engineer Peter Seton Hay, and is regarded as one of his greatest engineering achievements. Prior to Hay’s solution, many proposals for a route through the Southern Alps had been made, including one from a prestigious US engineer, Virgil Gay Bogue. All of these options were both expensive and steep, limiting the daily tonnage the route could support and increasing the risk of landslips and avalanches.

Hay offered the plan for the Ōtira tunnel as a counter proposal to Bogue’s report. Bogue agreed it was the superior plan and it was accepted. Sadly, Hay did not live to see it constructed, as he died of complications from exposure in 1907.

Engineering New Zealand CE Dr Richard Templer speaking at the centenary event. Photo: Engineering New Zealand.

Engineering New Zealand Chief Executive Dr Richard Templer spoke at the centenary, highlighting the value and importance of railways to New Zealand. He remarked that this would be especially true moving forward, as they play an increasingly significant role in decarbonising our economy in the face of climate change.

“The courage, vision and commitment of the people who spent 15 years working on the tunnel can be an inspiration to us as we tackle complex problems like climate change, environmental sustainability, and equality,” Templer said. “The engineering profession is committed to playing its part to work with all of society to solve these challenging problems.”

Many travelled to the event from Christchurch aboard a regular TranzAlpine rail service, and some unwitting passengers that day were likely surprised to encounter both staff and passengers dressed in 1920s era-appropriate clothing to commemorate the event. They were greeted at the station by the music of the Kokatahi Band – one of New Zealand’s oldest bands, founded in 1910.

As well as the ceremony itself, visitors were kept busy throughout the day with activities. A bus shuttled passengers to and from the Ōtira tunnel portal viewing area every half hour. Meanwhile, at the township itself, new information panels and a commemorative plaque were unveiled. A replica of a tunneller’s hut, which was built for the occasion, could also be visited. Many in attendance were former Ōtira residents, and historians were on hand to collect stories about peoples’ connection to the township and Arthur’s Pass.

Today, the tunnel is only the third longest in New Zealand, marginally shorter than the Kaimai and Remutaka Rail Tunnels. But in the early 1900s, the Ōtira Tunnel represented a simple if not ambitious solution for a coast-to-coast rail connection. The harsh conditions in which the tunnel was constructed and its ongoing contribution to the economy and West Coast communities remain a true testament to Kiwi engineering.