26 Sep 2024

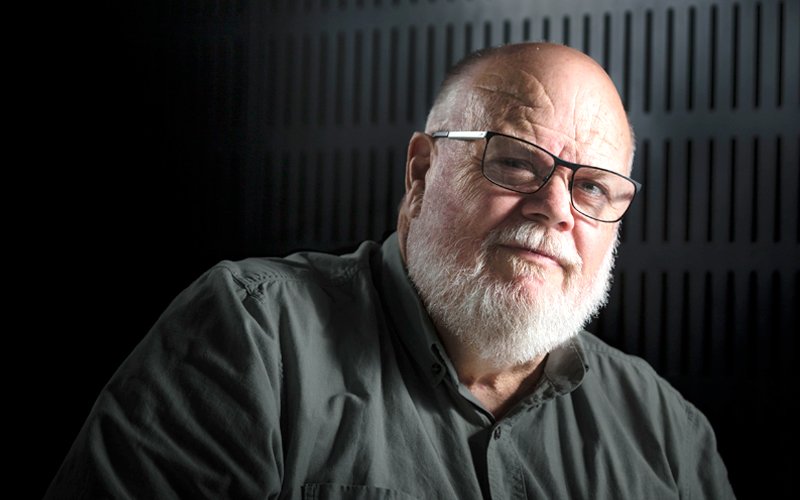

Dr Ron McDowall ONZM DistFEngNZ was an active and influential member of the engineering community in Aotearoa and abroad, held in the highest regard by his colleagues and peers. The following article, published in EG magazine in 2018, offers a glimpse into the passion and generosity that Ron showed in his work. His dedication to engineering, AI and sustainability never waned, and his passing is a great loss to his whānau and the engineering community. Ron passed away on Tuesday 17 September.

Dr Ron McDowall ONZM DistFEngNZ. Photo © Adrian Malloch

From the slide rule to the Singularity

Through his work in 126 countries with the United Nations, Kiwi engineer Ron McDowall became a world expert in hazardous toxic waste. But it took a heavy physical and emotional toll and nowadays he prefers to focus on the future – particularly sustainability and the Singularity.

Once there was a Kiwi engineer who saved millions of people from poisonous chemicals and the Queen gave him a medal in recognition of his great work. But as this is a true story, the “happily ever after” has some brutal caveats. Night terrors. Flashbacks. An old gunshot wound that still gives him trouble. A cache of horrific memories so disturbing he has never even told his wife.

When asked nowadays, Dr Ron McDowall ONZM FEngNZ CPEng IntPE(NZ) simply tells people he’s a professional engineer.

“But I’m a kind of multi-person these days – I still do engineering but I do a lot of teaching.”

The former Engineering New Zealand Board member teaches an MBA programme in addition to engineering and accounting, and jointly set up the Rutherford Business Institute, running courses for executives and consulting to large organisations and government departments.

But it’s through the United Nations (UN) work that he’s managed to help the most people.

"Because it matters"

While running an engineering consulting company in the 1980s, Ron got involved with dangerous chemicals and became part of a UN team of engineers and scientists removing hazardous waste.

“Our role was to go to developing countries and remove dangerous chemicals – pesticides, insecticides, herbicides, industrial chemicals and nuclear waste,” he says.

It was incredibly risky work.

“Of the 15 who were originally on the team, only three are still alive with the others dying from accidents related to the job. Some were kidnapped – particularly in Africa – some were poisoned by the chemicals they encountered, some were shot by terrorists in Northern Africa, one went missing in Northern Mali, never to be seen again.”

He recalls being in a physically and mentally bad way after one mission, in hospital back in New Zealand, questioning why he did this work.

His friend, the late David Thom FEngNZ, simply replied: “because it matters”.

Hazardous toxic waste expert Ron McDowall on United Nations missions. Photos: Supplied

The hazardous waste was often the result of a misguided attempt at help. Western democracies donated vast volumes of chemicals, such as pesticides, to developing countries.

“Tonnes and tonnes of this stuff were then distributed all over these countries, such as Tanzania, then left in storage because nobody knew how to apply it.

“Then after about two years the stuff is passed its use-by date and of course it’s dangerous as hell to humans. It just remains rotting in these storehouses all over the country and generally forgotten about until it leaches out into the soil into the growing areas and people start dying.”

His biggest project was in the Côte d’Ivoire in West Africa in 2006, the result of a chemical spill by a Dutch oil company.

He says one hundred thousand people sought medical treatment with awful skin lesions. “Children were dying, it was an absolute shambles.”

The team would fly to the affected area and work with European contractors who hired Russian Antonov aircraft filled with all the equipment for missions, including diggers, loaders and trucks.

Ron says all hazardous waste material – even chemicals from New Zealand – is shipped to France, where it is incinerated.

As for his most dangerous jobs, he cites Agent Orange projects in Vietnam and work with Hexachlorobenzene, which was “exceedingly dangerous – one slip of your mask and that was it”. And there were times when radiation levels were so high the team got “sunburnt”, suffering moderate radiation burns.

So how does he deal with the emotional and physical toll of the work?

“I always just look at what we achieved. We improved the lives of probably millions of people, all told… by removing those bloody chemicals out of their lives.”

Suddenly Sweden

Ron had always wanted to be an electrical engineer, but his career began earlier than he’d expected. In 1971 he was headhunted by a Swedish electrical company, now ABB, while building a high bypass filter during the second year of his electronics and physics study at The University of Waikato.

Unsure whether to take the role as he was only part way through his science degree, Ron consulted with his father, a man he describes as “one of the world’s greatest critical thinkers”, who died last year.

His father just asked him: “When do you leave?”

Within 10 days he was off, and he worked in Vasteras, Sweden for a decade while completing his studies in electrical engineering.

Ron spent much of his time in Sweden in a large, windowless room that was painted black from floor to ceiling, trying to predict the future.

“The idea was to cut you off from your worldly worries,” he says.

“We were going out 30, 40, 50 years and working out – postulating – what the world power grid system would need to look like so that we could backcast to the present and work out how to provide the equipment that such a system would require.”

Did they get it right?

“Did we what,” he says, particularly regarding a protection system for the world’s big power networks, the design of which was inspired by static from a transistor radio. But while the idea was foresighted in the 1970s, it couldn’t be designed until the dawn of integrated circuits.

Learning and teaching

After 10 years in Sweden, Ron returned home and co-founded a consulting management and engineering company. In the mid 1990s he started a PhD in Engineering Management at The University of Waikato and began teaching part time at the University of Auckland. He helped establish a Masters programme in the Faculty of Engineering focused on sustainability, complexity, engineering and management. In 2007 he joined the Faculty of Business to teach an MBA programme.

He doesn’t believe the way universities are teaching engineering is keeping pace with the ever-changing world.

“They are still all hammering the principles of engineering, math modelling and so on.”

While that is still required, algorithms are everywhere now, he says, predicting artificial intelligence will advance to such a degree “even a non-civil engineer will be able to design a structure by simply saying it needs to occupy this space and do this, and artificial intelligence algorithms will fully determine the design”.

Engineers need to be critical thinkers and high-stakes decision makers, Ron says, and they need to be taught how to make great judgement calls.

“Sustainability must happen.”

Ron used to worry about sustainability, until he realised it was inevitable.

“Sustainability must happen. It has to come, whether you like it or not.”

He tells engineers sustainability is complex.

“If it wasn’t we would have resolved it by now.”

He believes everything needs to undergo a paradigm shift – products won’t exist as they do now because there won’t be enough resources. But individuals alone can’t influence this paradigm shift – entire systems need to change.

Take lighting, for example.

“In the future there’ll be a photon capture unit on the roof that captures photons from the sun all day long and spreads them through the building at night when you need it.”

Or food and drink.

“If you go and drink a can of Coca-Cola it won’t be a can… there’s no aluminium left in 2050. It’ll be a nanosurface of the Coke itself so as you drink the Coca-Cola, you drink the can.”

He talks of food with pull tabs – one to freeze the item, such as a pie, the other to heat it.

And in the future there’ll be no plastic. Ron suggests wool could be the fibre of the future. He’s supervising a PhD student who is studying the future of strong wool, and a black room will be set up as part of the research. There, a question will be posed, such as: “It is the year 2052. Strong wool cannot meet the demand for the fibre. What is the fibre being used for?”

Transistors and transitions

While it seems like Ron has seen it all, he’s still keen to see more. When he started his career, all calculations were done on slide rules and there was valve technology.

“And as I come to the end of my career, which I hope is another 10 years from now, we’re going to be into artificial intelligence and the Singularity.”

The Singularity is the point when artificial intelligence surpasses human intelligence, something Ron has been studying since he began his PhD. He predicted the Singularity for roughly 2030, which is on par with the thinking of leading futurists.

“My career has occupied the entire spectrum of electronic systems, all the way to the internet of things to the Singularity. I’m expecting before I shuffle off this planet that I will see the Singularity.”