This piece is an excerpt from Take Me With You Too! A Self-Drive Guide to Dunedin’s Engineering Heritage, the second book by award-winning engineer and author Karen Wrigglesworth. Her first – about Whanganui – won an Outstanding Contribution to Heritage Award in 2020 and was Highly Commended at the Engineering New Zealand Heritage Awards in 2021. The Dunedin book was largely researched and written during a Robert Lord Writers’ Cottage Residency.

Gas has been an important source of energy in New Zealand since the Dunedin Gasworks opened at Andersons Bay Road in 1863. The Dunedin Gas Light and Coke Company (which established the Dunedin Gasworks) and the Auckland Gasworks Company were both established in 1862, but in the north the New Zealand Land Wars delayed construction in the country’s then-capital until 1865. Dunedin, however, was booming on the back of gold discoveries near Lawrence from 1861, and so the Dunedin plant was the first to become operational. It was also, serendipitously, the last to close, with operations ceasing in 1987 for gas manufacture at the site and in 2001 for LPG distribution.

Gasworks engineer Stephen Stamp Hutchison arrived in New Zealand in the early 1860s to oversee establishment of the Dunedin Gas Light and Coke Company. He had previous experience with both the London Gas Works and the City of Melbourne Gas & Coke Company, which supplied gas to Melbourne customers from 1856.

In Dunedin, manufactured coal gas – also known as town gas – was initially used for central city street lighting, with the original intention being to erect a small plant to supply fifty streetlamps. For ordinary citizens, the price of 25 shillings per 1000 cubic feet of gas (or 28 cubic metres in modern parlance) was prohibitively expensive, and most chose to stick with the more familiar – and more affordable – candle and oil lamp alternatives. But the gold rush boom was in full swing, and it quickly became apparent that more lamps – and a larger gasworks manufacturing facility – would be required. There was also a sharply increasing demand for gas from the new industries that were developing to serve the rapidly expanding, gold-rich town.

In July 1864, Hutchison acquired a six-year lease for the two-acre gasworks site in South Dunedin, as well as a contract with the Town Board to supply 150 streetlamps for seven years at a cost of £17 10s per lamp per year.

The gas streetlamps were designed by Town Board engineer John Millar (1807-1876). Born in Scotland, Millar worked on the Yan Yean waterworks in Melbourne in the early 1850s before moving (circuitously, via a return trip home to England) to New Zealand. He was appointed engineer to Dunedin’s Town Board in 1863 and reported strongly in favour of the Water of Leith for the town’s water supply instead of Ross Creek. In 1868, he reported on water reservoirs for the Otago goldfields.

Gas was first ignited at the Dunedin gasworks in May 1863, but a delay by the Town Board in erecting the lamp standards meant the first streetlamp was not lit until September.

The original 1863 gasworks complex included an arch-roofed retort house with adjacent set of condensers and a simple rectangular gasholder. A replacement retort house was constructed in the 1880s.

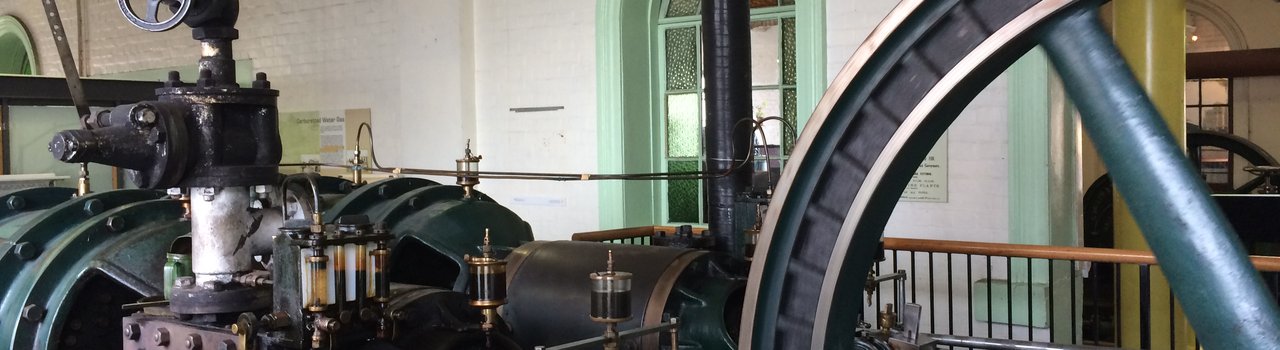

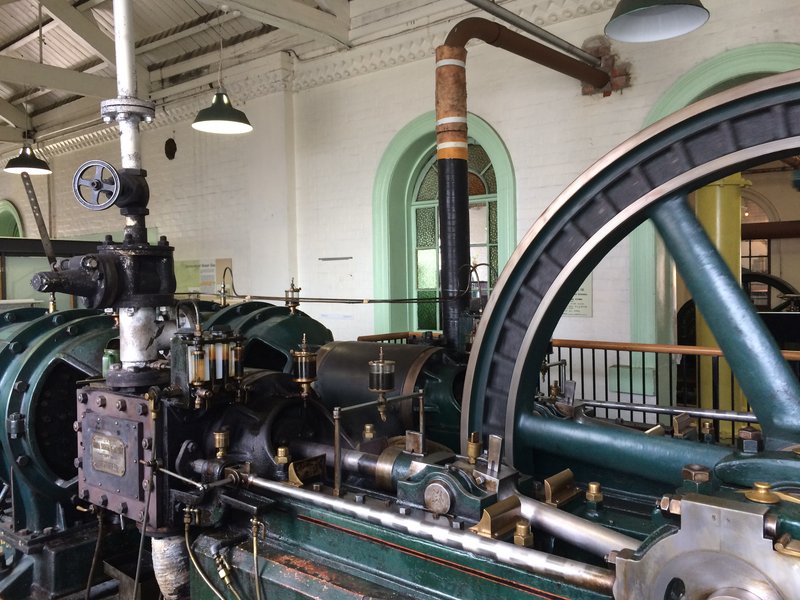

A small, stationary, steam-driven Garrison Foundry beam engine was installed at the gasworks in 1868. It was one of only two ever built at the foundry, and is now believed to be the oldest operational steam engine in New Zealand. The engine was built in Falkirk, Scotland and was the first of a series of increasingly powerful steam engines used to drive the exhauster pumps at the Dunedin gasworks. These drew gases out of the retorts (described below) and pumped them through the rest of the works.

The Garrison Foundry and Engine Works was founded by Thomas and Robert Blackadder in 1851. Their family had been involved with engineering and iron and brass foundry work since 1771. A son of one of the brothers, also named Robert Blackadder (d. 1900), emigrated to New Zealand around 1864, initially working for Kinkaid, McQueen and Co before establishing his own engineering machinery import business in the Octagon. It is possible that Blackadder brought the beam engine with him to Dunedin – according to the Falkirk Local History Group, the engine was exported to New Zealand in 1864.

Dunedin City Council purchased the gasworks plant from Hutchison in January 1876 for £49,400, spending an additional £50,000 for immediate improvements including a new retort house. The brick boiler room chimney – a South Dunedin landmark – was constructed around 1881.

Also in 1881, Hutchison obtained a charter to construct a second gasworks at Caversham. This facility was in operation by late 1882 and immediately went into competition with the Dunedin Gasworks that Hutchison had sold to the council six years earlier. This led to such furious debate around the council table about the letting of a contract to supply gas to Caversham, Mornington and Roslyn that a ratepayer and two councillors appeared in the Police Court for assaulting the mayor. In the end, Caversham Gasworks won the contract.

Caversham Gasworks was later sold to the Dunedin and Suburban Gas Coy Ltd and operated until 1909. It was demolished in the 1980s.

A purifier house was added to Dunedin Gasworks around 1900 but the equipment almost destroyed the works when a large explosion occurred in 1903. In 1906, a major gasworks upgrade saw both a new retort house and a 28 million litre gas holder constructed. The gas holder was moved to Wilkie Road in Kensington in 1915 after its bottom plates fractured due to unstable ground conditions, while the retort house was eventually extended to enable more gas to be made.

The gasholder legs and frame were returned to the South Dunedin gasworks site in 2000. The structure is inscribed ‘1879’, but its original installation at the Dunedin Gasworks site actually dates to 1881. Also engraved on the gas holder are the names ‘E Genever’ and ‘Horseley Co Ltd, Tipley, Staffordshire, England’. Genever was manager of the gasworks from 1876 to 1882, while the Horseley Ironworks was founded by Aaron Manby around 1815 in the English West Midlands.

Coal or town gas was made by heating coal in the absence of air in a large, enclosed chamber or retort – first to 400°C to remove water (as vapour), tar and ammonia, and then to 1,000°C to remove raw coal gas to create coke. Coke was in turn burnt to heat the retorts and as a fuel for heating homes.

The raw gas was then siphoned off and passed through one or more condensers (the large silver chambers in the gasworks yard) to remove coal tar and liquefy the gas, which was then purified (to remove ammonia – used in the dye and chemical industries), passed through a meter to measure its volume, and stored in a gas holder. Boosters fed the gas through a low-pressure distribution network to customers.

The tar by-product was collected in a tar well, then used to seal roads or further distilled to make creosote for wood preservation and weedkillers. The condensers were cooled by water tubes that can still be seen in the chambers today.

Exhausters followed the condensers in the gas-making process. These were driven by steam engines to pump the gases from the retorts through the rest of the works. Once again coke was used as a fuel to fire the steam engine boilers.

Next in the process came an electrostatic de-tarrer which used electrically charged plates to remove the final traces of tar from the gas. Purifiers removed the hydrogen sulphide, after which the gas was pumped to the gasholders for storage. From there, a governor was used to maintain the pressure in the gas mains network throughout the city as demand fluctuated each day.

As a gasworks, the Dunedin operation was designed to produce high-quality gas with low-grade coke as a by-product, but the process could also be set so a plant instead produced high-quality coke for metallurgical use, with lower-quality gas as the by-product.

Gas was initially produced for lighting, but with the advent of electricity, focus shifted to heating and cooking uses, and refrigeration. Gas for lighting was made by passing air over incandescent coals, giving a yellow, oily gas. To make heating gas (cleaner, but less luminous in burning), either less air or alternatively steam was passed over the hot coals instead.

Scottish engineer William Murdoch is reputed to have discovered coal gas by heating coal in his mother’s teapot. He later learnt how to make, purify, and store the gas – using it to light his home in 1792 and, from 1805, a Lancashire cotton mill. The first commercial gasworks was built in London in 1812.

Coal gas was a common commodity in the 19th and early 20th centuries, used for lighting, cooking, heating and industry. More recently, it has been used to manufacture medicines and saccharine.

New Zealand’s first coal mine was established at Dunedin’s Saddle Hill in 1849, followed by Kaitangata in 1858, and Green Island in 1861. Many other mines – most employing fewer than 20 people – opened in and around the city in subsequent decades. By 1900, coal was New Zealand’s main energy source.

Coal varies in quality depending in part on the original plant matter it is formed from. It results from compression over a long period – turning first into peat, then lignite (or low-grade brown coal), then sub-bituminous and bituminous coal (mid- and high-grade products respectively), and finally into anthracite. Otago coals are either low-grade lignite or sub-bituminous varieties, typically used for industrial heating.

In New Zealand, coal was originally transported by horse and cart or via coastal shipping. The country’s first narrow-gauge railway line, between Dunedin and Port Chalmers, opened in January 1873, and in 1876 work began on a dedicated railway siding off the Dunedin Peninsula and Ocean Beach Railway to bring coal directly to the gasworks site. At peak, around 15,000 tonnes of coal was railed to the gasworks each year.

In 1927, the original horizontal retorts at the gasworks were replaced with a Glover-West vertical retort house. Horizontal retorts had to be manually filled and emptied with shovels, whereas vertical retorts could be filled and emptied with help from gravity. The new facility also housed new exhausting and pumping machinery, and the pre-existing 1926 Bryan Donkin two-cylinder horizontal booster engine, which was used to supply gas at high-pressure into the distribution network during periods of high demand. Outlying governors were installed across the network, and a booster at the gasworks powered a duplex reciprocating compressor which could compress 2,800 cubic metres of gas per hour when required.

The Glover-West vertical retort house was replaced with a Woodall-Duckham vertical retort house in 1962, and the old horizontal retorts were removed. In 1964, an oil gasification plant was introduced which used electricity to produce gas by reacting coal with oxygen and/or steam at high temperatures without the need for combustion. However the 1973 oil crisis destroyed its economic viability and coal gas production continued.

Peak production arrived in the 1970s, with coal gas provided to over 18,000 Dunedin customers. But by the mid-1980s, gas use in Dunedin was in decline.

In 1981, the council investigated replacing coal with reformed Liquified Petroleum Gas (LPG) for fuelling the city’s gas supply, which involved conversion of the existing reforming plant. In 1986, the Dunedin City Council Trading Committee voted unanimously to convert entirely to the reforming of LPG, and the Dunedin Gasworks coal carbonising plant was shut down in 1987. It was the last coal carbonisation plant in the country when demolished in 1989.

In 1990, tempered LPG distribution was opted for, resulting in the creation of a fully automated plant and a reduced mains network. This continued until 2001, along with a small landfill gas-to-LPG conversion operation through until 2000. The council sold its gas production assets to Todd Energy (aka Nova Energy) in 1999.

Dunedin Gasworks Museum Trust formed in 1988 and the Gasworks Museum opened in 2001 on a site now just one-fifth of the gasworks’ original footprint. The museum is a significant world heritage site with some of the best-preserved, semi-operational gasworks infrastructure in existence anywhere.

All images courtesy of Karen Wrigglesworth

Copies of Take Me With You Too! A Self-Drive Guide to Dunedin’s Engineering Heritage are available directly from the author at https://karenwrigglesworthwriter.com/