Gold was first discovered in New Zealand near Coromandel in 1852. Over the next thirty years New Zealand’s gold rushes attracted huge numbers in search of instant wealth.

Mining of Mount Karangahake and at Waihī began in 1875, following earlier gold rushes in Collingwood and Takaka (1856), Otago (1861), Marlborough (1862), the South Island’s West Coast (1865), and Thames (1867).

Californian and Australian gold rushes in the late 1840s and 1850s affected Auckland’s population. To encourage people to stay in New Zealand, Auckland businessmen offered a reward of £500 to anyone who could find a paying goldfield north of Rotorua.

Soon Charles Ring discovered gold near Coromandel township. This gold rush was short lived because of the difficulty of extracting the gold from underground quartz deposits. However, in 1867 the discovery of gold at Thames saw the population surge to 18,000 people by the following year.

Learn more about New Zealand’s gold mining industry.

Māori in the region were opposed to the mining of their lands. In 1864 Sir George Grey appointed James Mackay with the task of negotiating peace with the Hauraki tribes, and in 1873 he was appointed Commissioner for Māori Affairs. Mackay is a controversial figure because he was aware of the presence of gold in the Ōhinemuri region and used various unscrupulous methods to persuade Māori to sign away their mining rights. After the last Māori chief had signed on 17 February 1875, the Ōhinemuri field was officially opened up to prospectors on 3 March 1875.

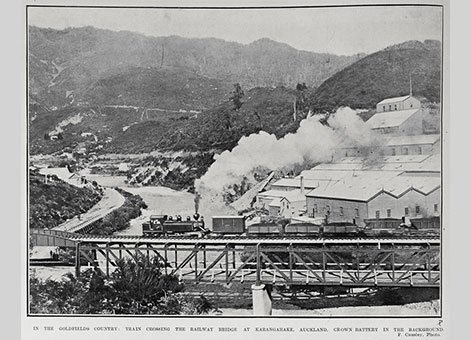

In the goldfields country: Train crossing the railway bridge at Karangahake, Auckland, Crown Battery in the background, 30 May 1907. Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries, AWNS-19070530-4-1.

A false start to mining at Mount Karangahake

At least 600 men raced into the area to peg claims on Karangahake Mountain. However, they were soon disappointed because gold was difficult to extract from the reefs using mercury amalgam. Therefore, most of the prospectors left within two months.

However, mining pushed forward in the last decade of the 19th century after the development of a new extraction process. In 1889 the MacArthur–Forrest process was introduced and the new Crown Battery soon became the world’s first field test of the cyanide process for the recovery of gold. This process was very quickly adopted by mining companies all over the region. Large capital investment was needed to mine and extract the gold, and soon there were three main companies exploiting the Karangahake resource, all with their financial headquarters in London.

It was around this period that the township of Karangahake expanded, establishing infrastructure, a school and a post office. In the early 20th century the population was around 3,000 but steadily declined as the gold resources depleted over the subsequent decades.

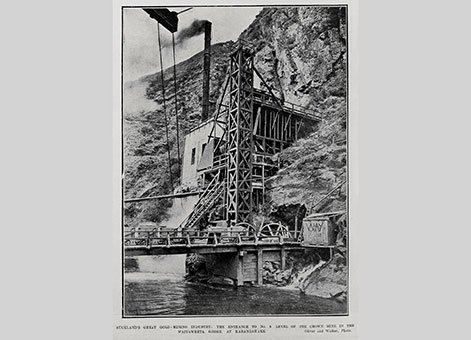

Auckland's great gold-mining industry: The entrance to No.6 level of the Crown Mine in the Waitawheta Gorge, at Karangahake, 4 November 1909. Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries, AWNS-19091104-10-5.

The mining companies

Cross section showing the extent of the Karangahake mining.

The Crown Company worked the Crown and Welcome Reefs, opening up six levels – the lowest being just above river level.

“The Crown reef was unusual in that it lay at around a 40 degree angle. The shaft was sunk on the reef so that it was described as an inclined shaft. The ore was hauled up with most of its weight on the wheels rather than on the winding rope of the conventional vertical shaft. In the higher workings the ore was broken out and dropped from level to level by “passes” to the river level, from whence it went by horse tram to the Battery.” (Ohinemuri Regional History Journal No 6 October 1966)

By 1916 returns were decreasing after having extracted 350,000 ounces (9.6 tonnes) of gold.

The adjacent Woodstock mine had five levels, but financial difficulties and pumping costs forced the closure of the mine in 1903, after 140,000 ounces (3.85 tonnes) of gold had been won.

The Talisman mine was formed in 1894 and in 1904 they took over the Woodstock mine, constructing new levels down to Level 13. This mine yielded 3,500,000 ounces of gold (96 tonnes) before going into liquidation in 1920.

In 1929 the Tallisman–Dubbo Goldmines Limited re-opened the Talisman mine, delving another three levels. However, by 1938 the ore was depleted and the mine closed in the following year after 57,000 ounces (1.56 tonnes) of gold had been won.

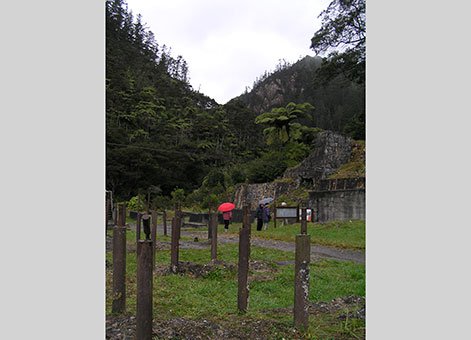

Powerhouse remnants at Karangahake Gorge, May 2012. Engineering New Zealand.

Environmental impact of Karangahake mining

The economic benefits of gold mining were off-set by social and environmental issues.

Gold extraction was environmentally very damaging. Timber was used for props in mines and as fuel for boilers, so it was not long before the surrounding countryside was deforested.

Local rivers also suffered. The mining waste tailings were dumped into the nearest river, and the silting and cyanide waste destroyed Māori fisheries. In 1895 the government declared the Ōhinemuri and Waihou Rivers to be sludge canals, which meant that mining companies were allowed to continue to discharge their waste into these waterways. Navigational problems also resulted and it became necessary to dredge the rivers. There was much opposition to the use of rivers for tailings and in 1909 the Silting Committee asked the government to revoke the sludge canal proclamation.

Heritage recognition

Aspects of the gold mining operations have been recognised by Heritage New Zealand.

Category 1 historic place (List no. 4673): Crown Battery Ruins: New Zealand Heritage List/Rarangi Korero information.

Category 2 historic place (List no. 7359): Woodstock Pump House and Battery: New Zealand Heritage List/Rarangi Korero information.

More information

Access

The Department of Conservation provides access information for the Karangahake Gorge Historic Walkway.

References

‘Gold Mining in Karangahake,’Ohinemuri Regional History Journal, Vol. 6, (October 1966).

‘Early Mackaytown,’ Ohinemuri Regional History Journal, Vol. 2 (October 1964).

JB McAra, Gold Mining and Waihi 1878 1952, Martha Press, Waihi, 1988.

Phil Moore and Neville Ritchie, Coromandel Gold: A guide to the Historic Goldfields of Coromandel Peninsular, Dunmore Press, Palmerston North, 1996.

Geoffrey Thornton, New Zealand’s Industrial Heritage, A H & A W Reed, Wellington, 1982.

GJ Williams, Economic Geology of New Zealand, Monograph Series No 4, Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, Victoria, 1974.

Location

The Karangahake region around the Karangahake Gorge on the Ōhinemuri River and the Waitawheta River area is traversed by State Highway 2, 8 kilometres east of Paeroa.