Completed in 1971, Manapōuri Power Station is an underground power station on the west arm of Lake Manapouri in the South Island’s Fiordland National Park. With 850 megawatt (MW) installed capacity, it is New Zealand’s largest hydro-electric power station.

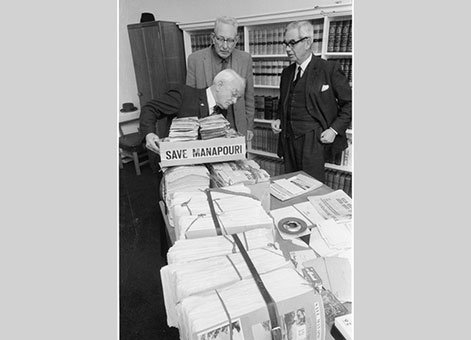

The Minister of Justice, Mr Riddiford, with Mr R C Nelson and Mr D McCurdy [26 May 1970]. Ref; EP/1970/2278/9-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

Power for industry

In July 1956, the New Zealand Electricity Department announced the possibility of a hydro-electric power project at Lake Manapōuri, and five months later Consolidated Zinc Proprietary Limited/Comalco Power Limited formally approached the Government about acquiring a large amount of electricity for aluminium smelting, more than any other single electricity user in the country.

On 19 January 1960 an agreement was signed between the company and the Government which aimed at creating New Zealand’s first significant attempt at an integrated electro-metallurgical industry. The Manapōuri–Tiwai Point electro-industrial complex involved the proposed power station and Tiwai Point Aluminium Smelter at the entrance to Bluff Harbour, more than 150 kilometres (km) away.

The agreement violated the National Parks Act, which provided for formal protection of the Fiordland National Park, and required subsequent legislation to validate the development. The agreement gave Consolidated Zinc exclusive rights to the waters of both Lakes Manapōuri and Te Anau for 99 years. The company planned to build dams that would raise Lake Manapōuri’s lake level by 30 metres (m), merging the two lakes and having significant environmental impacts on the Park. However, in 1963 Consolidated Zinc decided it could not afford to build the power station. The Government then took over the power station project and the company proceeded to build their smelter.

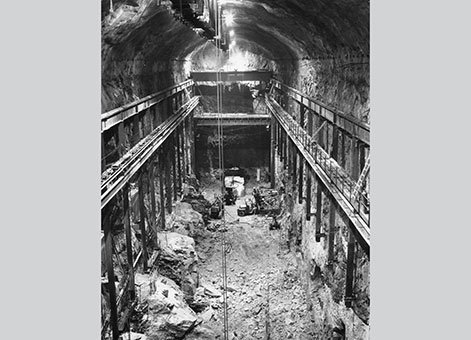

Machine Hall excavation, circa 1967, Image courtesy of L.Smith.

Construction

Building the power station started in 1964, with the three construction phases originally costing $135.5 million. The project involved almost eight million work hours and claimed the lives of 18 workers.

The location of the station utilises the 178m drop between Lake Manapōuri and Deep Cove in Doubtful Sound. Main contractors, Utah Construction and Mining Company excavated down 200m below the level of Lake Manapōuri, through hard rock, to build the power station’s machine hall between 1966 and 1968. This involved the removal of 1.4 million tonnes of rock. The machine hall excavation is 111m long, 18m wide and 39m high. The turbine-generator structure occupies the lower two-thirds with operating level and gantry cranes above.

The underground powerhouse has seven turbine-generators and their transformers. Cables in separate ducts feed power to the switchyard at the surface. Surface access to the machine hall is provided by a 2km spiralling vehicle tunnel or a lift that descends 193m from the control room.

Water for each turbine flows from the lake through screens and down vertical concrete-lined penstock shafts and discharges to a large draught tube manifold before entering the tailrace tunnels. The first tailrace tunnel was constructed concurrently, from Deep Cove portal, by joint venture contractor Utah-Williamson-Burnett.

Engineering versus the environment

The construction of the Manapōuri Power Station had wider implications for New Zealand’s engineering profession and is considered by many to be the birth of New Zealand's environmental movement.

In September 1969 the station generated power for the first time. Stage Two of the project involved the installation of three more generators and raising the lake level by 8m. The following month, the Save Manapōuri Committee was formed in Invercargill and soon led a national campaign to prevent the lake being raised because of the environmental impacts.

“Save Manapōuri” became the catch cry for scenery preservation, conservation and environmentalism, over commercially-driven industrial development. In 1970, the Save Manapouri campaign petition attracted 264,907 signatures opposing the raising of the lake, and in 1972 the Government decided against raising water levels at Lakes Manapōuri and Te Anau. This was a compromise between preserving the lake system and realising the hydro-electric potential of the Manapōuri Power Station.

Environmental considerations became an important aspect of subsequent civil engineering design and construction in New Zealand as a result of this project.

Machine Hall, 2005, Image courtesy of L. Smith.

Increasing capacity

Engineers found a design problem soon after the power station was fully commissioned in 1972. Greater than anticipated friction between the water and the tailrace tunnel’s walls reduced the hydrodynamic head – the potential energy per unit weight of fluid. Station operators risked flooding the powerhouse if they ran the station at an output greater than 585MW, which was well short of the designed peak capacity of 700MW. The power output capacity was also reduced by the decision to not raise the lake level.

Construction of a second tailrace tunnel commenced in 1997 and was completed in 2002. The original and second tunnels are 10km long, carrying the water to Deep Cove. The second tunnel is 10m in diameter and increased capacity to 850MW, although it is limited to 800MW due to resource consent conditions. The increased exit flow also increased the effective hydrodynamic head, allowing the turbines to generate more power without using more water.

Heritage recognition

The Manapōuri power station was added to the Engineering New Zealand Engineering Heritage Register on 6 March 2024. Read the Engineering Heritage Register report

Webinar recording

On 8 April 2024 we hosted a webinar to launch the Register Report.

Chair: Alan Brent, Professor of Sustainable Energy Systems, Victoria University of Wellington

Panellists:

- Keith Turner, Board Chair, Transpower.

- Brett Horwell, Head of Electricity Supply, Meridian Energy

- Caroline Rea, Civil Engineering Manager, Renewable Construction, Meridian Energy

Watch the recording below.

Find out more

References

“Manapōuri hydro station”, Meridian Energy, accessed 7 September 2015.

“Second Manapouri Tailrace Tunnel”, Electricity Corporation of New Zealand Limited (1996).

A Question of Power – The Manapouri debate (1980), NZonScreen, accessed 7 September 2015.

John Martin, People, Politics and Power Stations: Electric power generation in New Zealand 1880–1998 (Wellington: Electricity Corporation of New Zealand, 1998), 205–17.