The government operated electricity system in New Zealand evolved from the early 20th century with a first step being the construction of the Okere Falls Power Station, a hydro-electricity scheme to power Rotorua.

In 1903 the Superintending Engineer for the New Zealand Public Works Department (PWD), Peter Seton Hay (1852–1907), investigated and reported on the hydro-electric potential of New Zealand. Following later were reports to the Minister of Public Works by engineer Lawrence Birks (1874–1924) in 1910, and Chief Electrical Engineer Evan Parry (1864–1938) in 1918. These reports were the basis for the government's involvement in electricity, in particular the planning and construction of hydro-electric stations at: Lake Coleridge, Mangahao, Waikaremoana and Arapuni.

Tekapo B Power Station, July 2004. Photograph courtesy of R. Aspden.

Prior to 1914, about 20,000 kilowatts (kW) was generated from 13 power stations run by local authorities, private companies and private individuals. In 1915, electricity generation commenced at Lake Coleridge, which had an installed capacity of 6,000 kW. This was subsequently increased to 34,500 kW by 1930. Coleridge marked the government's entry into electricity supply.

Parry's 1918 report covering the proposals for the North Island stations at Mangahao, Waikaremoana and Arapuni also envisaged 1,421 miles of transmission lines and 26 substations. First power from Mangahao was generated in 1925, from Waikaremoana in 1929, and from Arapuni in 1932. Parry's report was far reaching, and fundamentally shaped the country's electricity development. During the construction of these early stations, engineers were confronted with the complex geology and difficult foundation conditions, which were a feature of practically all New Zealand's subsequent power projects.

In 1925, investigations into South Island requirements were carried out by: Frederick Templeton Mannheim Kissel, George Pellew Anderson (1882-1948) and E W McEnnis.

The Waitaki Station immediately above Kurow was constructed between 1928 and 1934. Initial generation was 75 megawatts (MW), subsequently increased to 105 MW in 1954. Waitaki was the last major dam project constructed by picks, shovels and wheelbarrows, manual methods being deliberately adopted to occupy the unemployed. Working conditions were not good. The site was isolated, windswept and extremely cold in winter. By the end of the project there had been 1,864 compensation payments for death or injury. There were 11 fatal accidents.

Clyde Power Station, November 2009. Photograph courtesy of R. Aspden.

Electricity shortage and expansion after World War Two

At the beginning of World War Two, the Hydro-Electric Branch of the PWD was generating 280 MW from eight hydro-electric stations and two coal fired steam power stations. The network of transmission lines had been considerably extended. Investigations into the development of the Waikato River were completed.

During the war years design and construction were carried on under restrictive conditions. Electricity demand was increasing steadily. Immediately after the war restrictions on supply became severe. A return to high rates of expansion was anticipated. An increase in transmission voltage from 110 kilovolts (kV) to 220 kV was being considered. A construction town was established at Mangakino to service the hydro development of the Waikato River. Investigations continued in the South Island on major rivers such as the Waitaki and Clutha.

A 1947 film, Power from the River, highlighted the limitations of the North Island's electricity supply, especially during peak evening hours, and promoted the construction of Waikato River power stations to supplement the supply from Arapuni.

In the post-war years the anticipated explosion in the use of electricity took place, and the next 30 years saw an 11-fold increase in the capacity of the generating system, from 500 MW to 5,600 MW. In 1946 the State Hydro Electric Department was created and took over the PWD's responsibility for electricity generation, transmission and sale of bulk power to the local distributing authorities. The PWD continued to provide design and construction services in the civil engineering, hydrological and hydraulic aspects of power projects. The State Hydro Electric Department subsequently became the New Zealand Electricity Department and the PWD became the Ministry of Works (MoW).

Critically important events during this period were the power crises of the early 50s when serious shortfalls in supply created shutdowns and blackouts throughout the country. These were a regular occurrence in the years between 1954 and 1957 and gave rise to great public concern, which was fully recognised by the governments of the day. Programmes for the construction of new hydro stations were already under way in the North Island, but the growth in demand was such that more comprehensive measures were required.

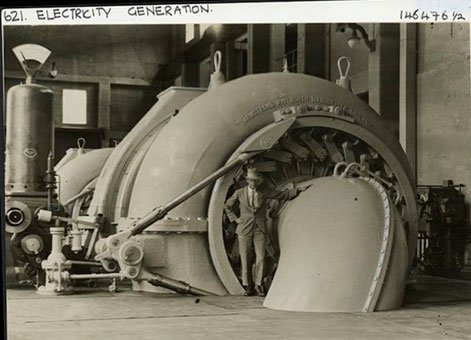

Photograph of man beside turbo-generators in a Waikaremoana hydro-electric power station, Hawke's Bay, circa 21 November 1929. Ref: PAColl-8377. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

In 1955 the Government set up committees for assessing power needs and for planning the construction of new power stations. These committees met and reported annually to Parliament over a period of 30 years until deregulation and repeal of the Electricity Act in 1987–88.

As a result of these annual planning procedures, and their acceptance by Government, large scale construction programmes were set up in both North and South Islands. Skilled personnel were recruited from oversees to augment the existing workforce.

In the North Island eight hydro stations were constructed on the Waikato River, one on the Rangitaiki, and two associated with the Tongariro Power Development. Output from the eight Waikato stations was increased about 18 per cent by the Tongariro water diversions. Two geothermal stations, five fossil fuelled steam stations and three gas turbine stations were also constructed.

In the South Island two hydro stations were constructed on the Clutha River, six on the Waitaki, one at Manapouri, plus five lake control dams. At times up to five power stations were under construction at the same time.

Considerable skill in the design and construction of hydro-electric and thermal power plants was built up over the 30 year period of intensive development. A HVDC transmission link, the first in the world of its size, was established between North and South Islands to enable the abundant hydro power from South to be available to consumers in the North. Funding for the programmes was on a user pays basis, ie loan repayment and interest charges were financed out of bulk tariff revenue. Tax revenue was not used.

It should also be noted that, throughout the 30 year post-war period, the country was never entirely free of the need for some measure of restraint on use of electricity. Restrictions on certain non-essential items, such as street lighting, were required from time to time because of dry year reductions in hydro-electric output. This is contrary to the belief in some quarters that there was considerable surplus capacity resulting from overbuilding during the period.

Maraetai Hydro power station, Waikato River, 6 January 1976. Whites Aviation Ltd: Photographs. Ref: WA-72997-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

Late 20th century electricity in New Zealand

In this way the critical shortages of the 1950s were overcome. The resulting system consisted of approximately 75 per cent hydro-electric and 25 per cent thermal capacity. In dry years the reduction in hydro generation could be made up by increased thermal generation. The transmission link between North and South Islands permitted the most efficient use of water and fuel resources. The energy produced ranks amongst the cheapest in the world, and is primarily from renewable non-polluting resources.

Although the government stations supplied the majority of the energy, new generation was not confined to their NZED stations. Local distribution authorities continued to initiate their own schemes where favourable local resources existed, such as economic small hydro potential.

Electricity demand followed an exponential growth rate exceeding seven per cent annually until a levelling off in the late 1970s. In the closing years of the 20th century, growth rates were less than half the earlier figures.

In the 1980s government policy moved strongly towards reduced state involvement in development. Electricity development was no exception. The NZED, after a period of about six years as a Division of the Ministry of Energy, became a state-owned corporation, the Electricity Corporation of New Zealand (ECNZ).

The transmission branch of the department was separated off to become another state-owned company, and controller of the grid, Transpower. The government construction agency, the MoW, was dismantled and sold off, and the power planning procedures replaced by the creation of an electricity market. The last Government power station to be commissioned was Clyde in 1992. The breakup of ECNZ began in 1996 with the creation and subsequent sale of Contact, a group of stations representing 30 per cent of ECNZ's generating capacity. The remaining portion was split into three separate companies in 1999. Therefore, the planning and construction of new generating stations is now in the hands of private enterprise, as it was in the early 1900s.

The history of the government's role in electricity development as outlined here is well summed up by the following quotation from the publication People, Politics and Power Stations:

"As some have observed, it might appear that the wheel has turned full circle. However, the world we live in today bears little resemblance to the pioneering days of electricity in New Zealand. What is unquestionable is that, by its 100 years of involvement in the electricity industry of the country, the government and its various departments of state have put their stamp on what we are today."

More information

Source

Bill M Duncan, “An overview of New Zealand's electricity system, 1908–1999,” adapted for IPENZ’s Engineering Heritage Record by Rob Aspden and Karen Astwood, 2011.

Further reading

John E Martin, People, Politics & Power Stations, ECNZ, 1991.

William Newnham, Learning Service Achievement, New Zealand Institution of Engineers, 1971.

Evan Parry, 'The economics of electric-power distribution,' New Zealand Journal of Science and Technology, January 1918.

Additional image gallery details

Photograph of man beside turbo-generators in a Waikaremoana hydro-electric power station, Hawke's Bay, circa 21 November 1929. Ref: PAColl-8377. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

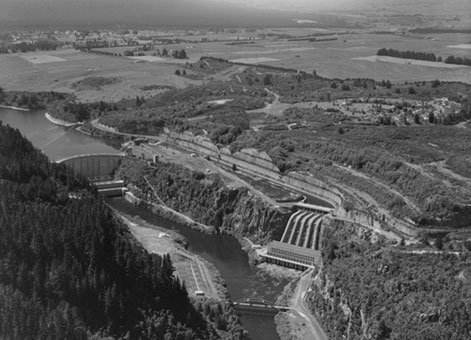

Maraetai Hydro power station, Waikato River, 6 January 1976. Whites Aviation Ltd: Photographs. Ref: WA-72997-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, must be obtained before any re-use of these images.