Built between 1871 and 1884, the Ōamaru Harbour Breakwater allowed ships to berth safely, strengthening Ōamaru’s development into a highly prosperous Victorian town.

Rough seas pound Ōamaru’s coast. Shipwrecks were common and one storm in 1867 left three ships wrecked on the beach. The following year another storm sank two wool ships and a coaster.

Wool, grain and from 1882 frozen meat, were the produce that brought wealth to North Otago. The provision of a safe port was central to Ōamaru businessmen’s vision for the development of their town. The grand harbourside buildings built of local limestone stand as evidence of this prosperity and confidence.

View of the breakwater extending into the Ōamaru harbour, ca 1880s. Burton Brothers (Dunedin, N.Z.). Ref: 1/2-C-22767-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/23010554

Creating a safe harbour for ships on such an exposed coastline provided many engineering challenges. The original plan was to create a small gated dock in the mouth of the Ōamaru Creek, known as the Brewery lagoon. But concerns that shingle would quickly build up around the dock entrance led to the addition of two long sea walls that would shelter the entrance to the dock. Attention and money turned to the construction of this breakwater. The breakwater would in effect create a sheltered harbour and the dock project was abandoned.

Construction begins

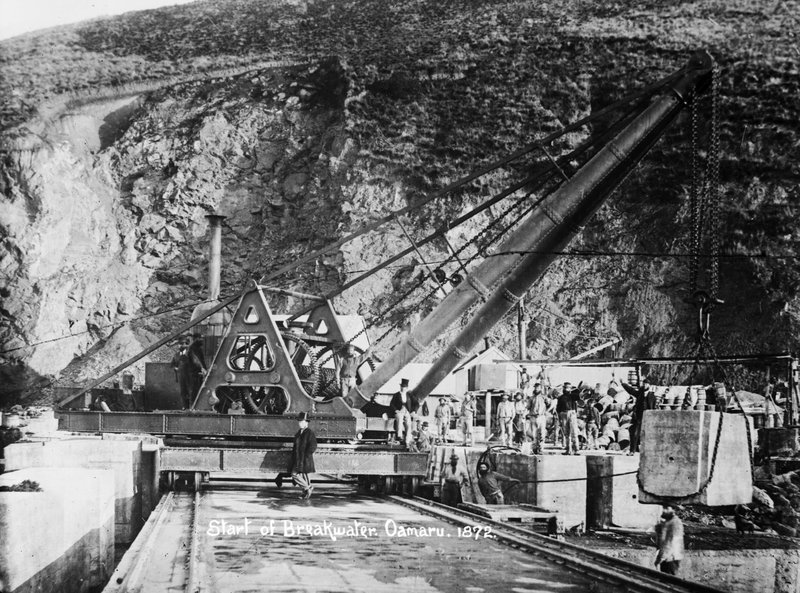

Work began in 1871 with the manufacture of a concrete mixer and the casting of about five concrete blocks. The breakwater was designed by Scottish harbour engineer, John McGregor. The contractors for the first two stages of the construction were Walkem & Peyman of Dunedin.

The first section, of about 240m, was made of two rows of concrete blocks with rubble filling the space between them. Beyond this, to combat the rougher seas, the wall was solid concrete blocks. Concrete was necessary as Ōamaru’s local stone was too soft to last long against continued wave action.

Gravel for the concrete was harvested off the beach and the concrete was mixed with salt water. The cement came in wooden casks, each weighing 180kg. A total of around 40,000 casks were used. Every sailing ship that came to Ōamaru from Britain carried some cement, and the supply, budgeting, storage and cost of this English-made cement was a constant nightmare of administration.

Disposing of the empty casks was a project of some magnitude. Casks in good condition were sold, and the rest left on site. It is estimated there are some 5,000 casks filled with rock and dirt under the penguin colony buildings which now sit at the base of the breakwater.

To transport materials to the site of construction, a tramway was built along the coast. Rock was blasted from the base of the cliffs and land reclaimed to create a narrow shelf on which the rail line could run. Storm waves swept over the line at high tide.

For many years after the completion of the breakwater the line was operated by New Zealand Railways.

The 'Moa' travelling crane, photographed in 1900. Collection of the Waitaki District Archive. Id 102066. Culture Waitaki Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence.

To lift the heavy concrete blocks and set them in place, contractors Walkem & Peyman ordered a rail-mounted steam powered crane from Dunedin engineering firm, Kincaid, McQueen & Co. It was variously reported in the papers as the largest, or second largest in the world. With a reported lifting capacity of 40 tons it certainly dwarfed most steam cranes of its time which commonly had a lifting capacity of two or three tonnes.

Another challenge was the composition of the seabed, which in some places was soft, allowing the concrete blocks to move with wave action. Divers were employed to prepare the sea floor by guiding a type of dredge and suction nozzle to remove the sand and expose the rocky bed.

Ōamaru Harbour, 1880s, Dunedin, by Burton Brothers studio. Te Papa (C.014146)

As the breakwater advanced a wharf was built alongside, allowing passengers to disembark directly rather than tempt the surf boats. The Macandrew Wharf opened to much public admiration in 1875. Further wharfs, Normanby Wharf and Cross Wharf were opened in 1878 and 1879 respectively.

After some trial bores in 1879, it was discovered the harbour could be dredged. This would turn Ōamaru into a deepwater port able to accommodate large ships from Britain.

The breakwater was completed to its full length in 1884 and Sumpter Wharf, a large export wharf, opened that same year.

Ōamaru suffered through the Long Depression of the late 1880s and 1890s, never recovering its earlier confidence.

Growth stopped, but maintenance and repair of the breakwater was an ongoing cost. An extension was begun in the 1930s, but by 1944, the project, still incomplete, was abandoned. Ships continued to call at Ōamaru until 1974.

Today the breakwater provides safe haven for small private boats and is recognised as a heritage precinct.

More Information

Heritage Recognition

The Ōamaru Harbour Breakwater and Macandrew Wharf is recognised by Heritage New Zealand as a Category 1 historic place (List no. 4882):

Ōamaru Harbour Breakwater and Macandrew Wharf: New Zealand Heritage List/Rarangi Korero information.

Ōamaru Harbour is recognised by Heritage New Zealand as an Historic Area. (List no. 7536):

Ōamaru Harbour Historic Area: New Zealand Heritage List/Rarangi Korero information.

Access

The breakwater can be viewed from the shore along the Esplanade or Waterfront Road.

The penguin colony is located at the end of Waterfront Road, near the base of the breakwater.

Further reading

McLean, Gavin. Kiwitown's port: the story of Oamaru Harbour. Dunedin: Otago University Press, 2008.

'Oamaru Harbour', (Ministry for Culture and Heritage), updated 20-Dec-2012.

Location

Ōamaru Harbour Breakwater and Macandrew Wharf

Page last updated 13 September 2019