Begun in 1943, Stony Batter was to be part of Auckland's defences during World War Two, but it was not completed by war's end in 1945. Located on Waiheke Island in the Hauraki Gulf, this was Auckland's last coastal defence fortress.

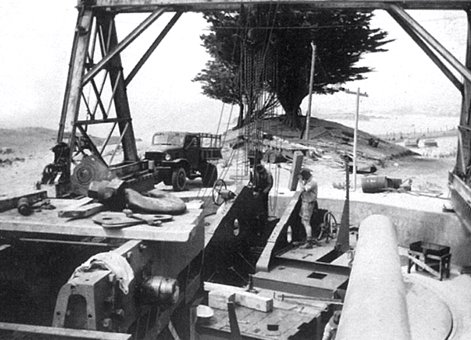

Construction work for 9.2 inch gun installation. Image courtesy of the Department of Conservation

Auckland’s coastal defences

By the 1920s, like others around New Zealand, Auckland’s coastal defences were obsolete. Many of the forts dated from the 19th Century and the most modern installation was a 6-inch battery at North Head built in 1905.

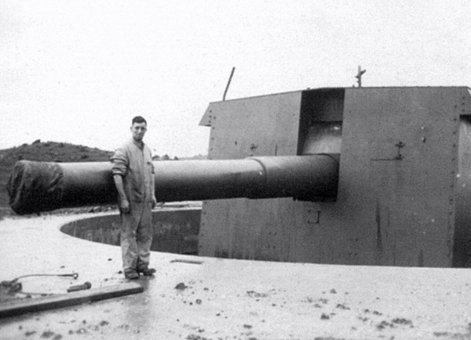

The main concern for military planners was that these older defences were too close to the ports they were meant to defend, and modern war ships could have shelled the city with little fear of counterattack.Auckland’s defences needed to be upgraded and plans were prepared for a new chain of forts to protect the harbour. The most impressive of these planned fortifications were to be 9.2-inch batteries. These guns were the largest commonly used for coastal defence but they were very expensive. For this reason the batteries were not built immediately and Auckland’s main defence throughout the Second World War came from a modern 6-inch battery built on Motutapu Island in the late 1930s.

The situation completely changed in December 1941 with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour and the subsequent entry of the United States of America into the war.

The government was prepared. Three months before Pearl Harbour a report had been written by General Sir Guy Williams (1881–1959) giving a higher priority to coastal defence, mostly as a precaution against raiders. An important part of this report was the recommendation to start construction of the larger 9.2-inch batteries shelved earlier because of cost.

However, there was a new problem in carrying out Williams’ recommendations, because there was no guarantee of a firm delivery date from the over-stretched British manufacturers of the equipment. In a significant development for New Zealand’s future international relations, this problem was resolved by the United States Navy. As part of the planned counter-offensive in the Pacific the Hauraki Gulf was to be used as a secure fleet anchorage, which required extended coastal defences. This altered the priorities of the British manufacturer. Delivery dates were set and work on the 9.2-inch batteries began.

9.2 inch gun at Stony Batter, Image courtesy of Department of Conservation.

Design

The design work was placed in the hands of New Zealand’s Public Works Department (PWD). It had been usual to this date for coastal defences, like the battery on Motutapu Island, to be built using designs sent from Britain. However, the situation in New Zealand at this time required another more localised engineering solution. British batteries at the time included a system of layers of concrete and steel burster slabs used on the surface of a fortification to detonate projectiles before they could penetrate deeply enough to cause damage, so protecting the underground magazines and services. The type of steel needed was virtually unobtainable in New Zealand so Stony Batter’s three batteries were redesigned locally as tunnelled rather than built structures, with the depth of the excavations rather than concrete and steel providing overhead protection.

To standardise the batteries, and to speed up work, existing PWD designs were chosen and modified. All the larger underground chambers were based on the double track Tawa Flat railway tunnel, while the smaller access tunnels followed standard railways personnel tunnels. At Stony Batter the local volcanic boulders, from which the site gets its name, were crushed and concrete mixed and pumped to the mobile steel and timber formwork which lined the tunnel sections.

Each of the batteries was originally designed for three 9.2-inch guns with deep underground magazines to store ammunition. Associated with these were pumps to provide the hydraulic power to move the guns and to work the automatic ammunition rammers that fed the heavy shells to the guns. To supply electricity for the fort, engine rooms were built deep underground, each with two large and one smaller Ruston Hornsby diesel engine. These were linked to generator sets and oil storage and exhaust systems were built nearby. All this was linked by hundreds of metres of personnel tunnels, with long flights of stairs and access from both the gun pits and at ground level.

Stony Batter tunnel vents near entrance, 5 November 2012. IPENZ.

Building Stony Batter

Three of these 9.2-inch batteries were built in New Zealand; two in Auckland and one at Wright’s Hill in Wellington. The Auckland batteries were located at Whangaparaoa and at Stony Batter on Waiheke Island. The battery at Stony Batter was in an inaccessible island location and it was impossible to get a private contractor who was willing to manage the difficulties of the site. For this reason Stony Batter was built by the PWD.

By October 1943 work had started. The initial intention to complete construction within twelve months proved to be hopelessly optimistic and the requirements for materials and skilled labour were never met. These problems were compounded by design changes and other difficulties brought about by wet weather. One particularly vexing problem was the access tunnels had been made with corners too acute to get the generator base plates into the engine rooms. Parts of the tunnel network had to be rebuilt to get around this dilemma.

Another problem that developed as the work progressed was a lack of proper financial control. This inevitably led to large cost overruns and it is difficult from the surviving records to calculate the true cost of this enormous complex. Years later, in 1982, Ministry of Works’ staff estimated the construction cost of the battery as being $13,600,000.

Progress on the construction reflected events overseas. At the time work began the Japanese posed a real threat and it was given the highest priority. As the threat diminished the job was scaled down. The first sign of this was in 1943 when the reduction of the battery's armament was suggested. This came about in 1944 when the numbers of guns for each fort was reduced from three to two. By 1945 the government had new priorities and large numbers of workers were transferred to other work building the hydroelectric power stations on the Waikato River.

Construction continued slowly after the war. In 1947 it was recommended that only the most essential work be completed. This included the pump chambers being fitted out so the guns could be operated, the main engine room completed, and a general tidy up be done prior to the battery being placed on a “care and maintenance basis”. The guns were not officially proof fired until 1951, although there is evidence that an “unofficial” test firing was carried out in 1946.

Stairway in Stony Batter tunnels, 5 November 2012. IPENZ.

Early retirement and a new life

In 1955 all material that would be liable to deteriorate was removed from Stony Batter, an event which signalled the end of the battery's military use, only a few years after its completion. By this time the cold war heralded an era of nuclear threat, long-range aircraft, and intercontinental ballistic missiles, so the old form of coastal defence seemed outmoded. Taking the lead from Britain, New Zealand wound down its coastal defences and the associated regiments were disbanded. By 1962–63 this process was almost complete. Stony Batter was stripped of its remaining equipment and abandoned, the only one of the three 9.2-inch battery installations to suffer such a fate.

Stony Batter is now a Historic Reserve looked after by an enthusiastic restoration society. The Stony Batter Protection and Restoration Society formed in 1999. Through their efforts access to the site and recognition of its heritage values has improved, leading to an increase in visitor numbers.

Heritage recognition

This place has been recognised by Heritage New Zealand as a Category 1 historic place (List no.7472):

Waiheke Battery: New Zealand Heritage List/Rarangi Korero information.

Find out more

Access

This is a Department of Conservation historic reserve. For access information refer to their webpage on Historic Stony Batter, Waiheke Island.

http://www.doc.govt.nz/parks-and-recreation/places-to-go/auckland/places/waiheke-island/stony-batter-historic-reserve/]

Source

David Veart, 'Stony Batter: Auckland's last fortress', in John La Roche (ed.), Evolving Auckland: The city's engineering heritage, Auckland, Wily Publications, 2011, pp.223–26.

Location

Stonybatter Road, Stony Batter Historic Reserve, Waiheke Island, Auckland.