Much of the gold in the Thames area lay in quartz veins below sea level. Large pumps were needed to remove water from these deep mine shafts, allowing the gold to be extracted.

Gold mining was big business in Thames in the 1870s. Huge sums of money were spent on plant and machinery to extract the precious metal. As mining companies extended their shafts deeper and deeper, extracting water from the mines became a greater problem. The solution was to commission what became known as the ‘Big Pumps’.

The Big Pump

In 1871 an association of four mining companies, called the United Pumping Association, engaged civil engineer, William Errington to draw up plans for a pumping system. Errington sourced a Bull direct action pumping engine with a steam cylinder 2m in diameter with a 3m stroke. Three Cornish boilers, each almost 10m long, supplied the steam.

The pump was capable of lifting almost 6,000 liters per minute from a depth of just over 300m, though was likely never run at this capacity. In 1883 the pump was reported as lifting 2,500 liters per minute from a depth of almost 200m, with greater boiler capacity needed if the engine was to be run at full power.

Installed in the Imperial Crown Mine, the pump was incredibly successful in dewatering many of the surrounding mines as well as those of the participating companies. At the time this was the largest pump in Australasia and among the largest in the world.

The pump was expensive to run and mining at lower levels had proved disappointing. Central government had been contributing to the cost of running the Big Pump but stopped these subsidies in 1878. The following year the Thames Borough and County Councils also stopped their financial support. Pumping at deep levels stopped and water levels were allowed to rise.

The operation was refinanced in 1880 and the pump continued to work intermittently until 1890 when it was closed down and dismantled.

Rediscovery of the Big Pump mine shaft

Covered over for more than 100 years, the shaft that contained the Big Pump was unearthed in 2012 after a pothole developed in the sealed roadway of State Highway 25, Queen Street, Thames. Local historians completed an investigation, revealing the massive stonework foundations. The site was confirmed as the location of the Big Pump before being recovered and the roadway repaired.

Thames Hauraki Pump - Queen of Beauty Shaft

In 1895 the Thames-Hauraki Goldfields Company acquired the Queen of Beauty mine. They aimed to install machinery that would allow them to pump to a depth of 610m. They ordered pumping machinery from England, and with the assistance of a government subsidy, enlarged the mine shaft in preparation for its installation. With the equipment ready, an official opening was held 20 December 1898. An enthusiastic report in the newspaper described it as the ‘finest pumping plant south of the equator’.

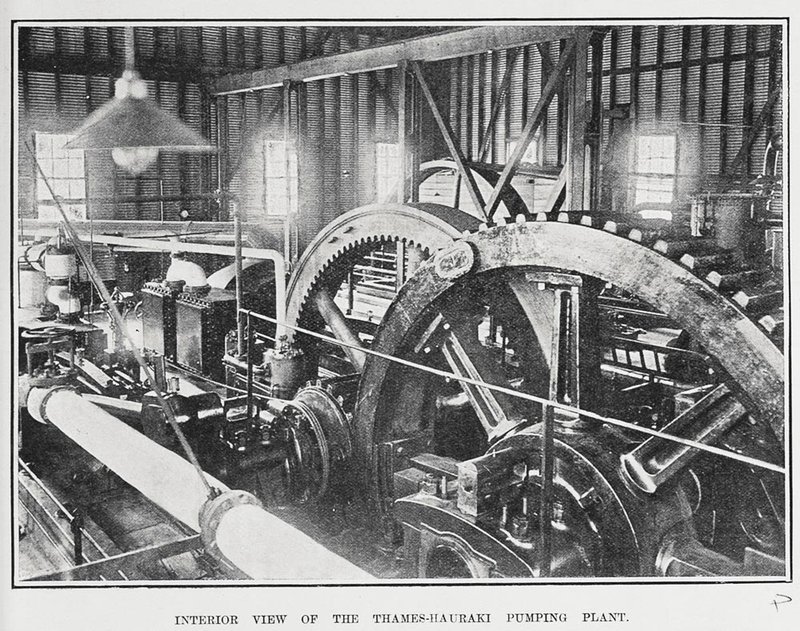

The pumps had three lifts from two pairs of 63cm diameter plungers each with 1.8m strokes. Each lift brought water up approximately 100m. To produce the required energy, ten boilers were arranged side by side feeding a pair of compound steam engines with high and low pressure cylinders of 76cm and 1.5m respectively.

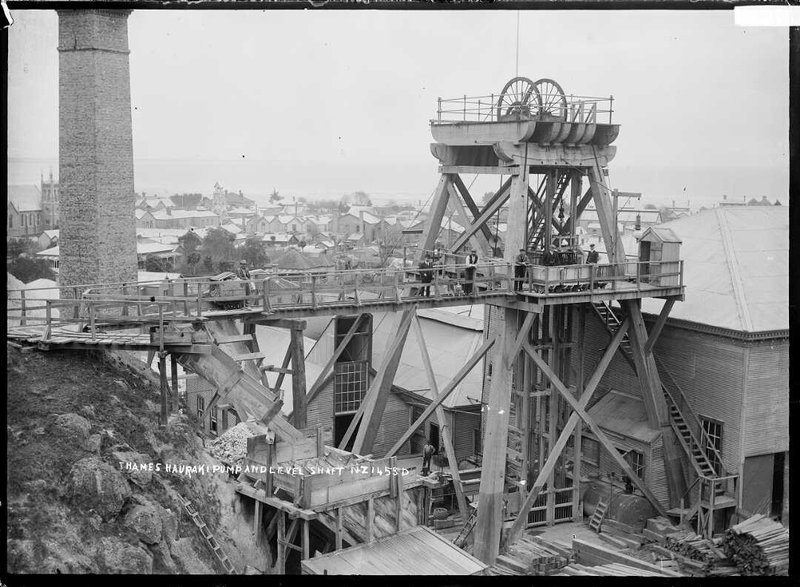

Thames-Hauraki pump and level shaft. Ref: 1/2-001558-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/22576601

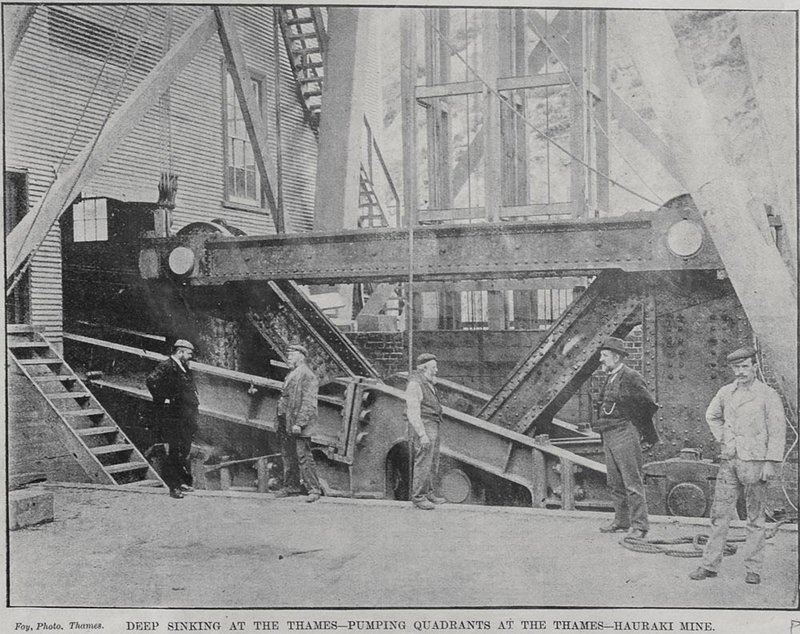

Deep sinking at the Thames-Pumping quadrants at the Thames-Hauraki mine. Auckland Weekly News 04 November 1898, p2. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections AWNS-18981104-2-2

The work of widening the mine continued after the official opening. By 1899 the shaft had been enlarged to a depth of 161.5m and by the following year had been widened to the bottom of the shaft at 228.6m. Further excavation was planned but was delayed due to a dispute between the nearby May Queen Company about water levels in their mine and their contributions to the costs of the Thames Hauraki pump.

With a Government subsidy in 1909 excavation continued to a depth of 311m. In an effort to find gold, a crosscut drive at 305m depth was launched. With £5,000 in government funding and £12,000 from the associated companies, work continued until 30 September 1913 when workings intersected a fault and water flooded into the workings. The miners were forced to retreat, and all work was suspended.

Gas seepage from the crosscut was another problem facing the mine and in 1914 this forced its closure. Pumping ceased. The Mines Department took control of the plant, and in 1918 plant and machinery was sold by auction. The two quadrants, each weighing 22 tons were too heavy to remove and these remain as a legacy to the massive pumping equipment installed at this site.

The property is now managed by the Bella Street Pumphouse Society Inc. who have restored and re-created some of the old machinery.

Interior view of the Thames-Hauraki pumping plant. Auckland Weekly News 19 January 1905 p3. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections AWNS-19050119-3-2

More Information

Heritage recognition

Queen of Beauty Mine Pump Quadrants is a Heritage New Zealand Category 1 historic place (List no.4682). Go to www.heritage.org.nz/the-list/details/4682

The Thames-Hauraki Mine Pumphouse is a Heritage New Zealand Category 2 historic place (List no.7684). Go to www.heritage.org.nz/the-list/details/724

References

Appendices to the Journals of the House of Representatives. Mines Statements 1871-1915.

"Imperial Crown Gold Mining Company." New Zealand Herald, November 1, 1871.

"Mining." Thames Guardian and Mining Record, November 16, 1871.

“Gold Mining in New Zealand: Pumping Station, Imperial Crown Mine.” The Engineer, March 13, 1874, pp179-180.

"A gigantic work." Auckland Star, December 20, 1898.

"The Goldfields." Auckland Star, September 30, 1913.

Arbury, David. “Thames Hauraki Pumping Plant.” Thames Goldfield Information Series, no. 15 (2000). Metallum Research Ltd., Thames, NZ.

Furkert, F. W. Early New Zealand Engineers. Wellington: Reed, 1953.

Williams, G.J. (ed.) Economic geology of New Zealand. Monograph series no. 4. Parkville, Australia: Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, 1974.

Access

The Hauraki Thames pump quadrants can be viewed at the Bella Street Pumphouse Museum, 212 Bella Street, Thames. Along with displays and photographs, the museum has a working model of the pumps and their driving steam engine.

Location

Bella Street Pumphouse Museum

Entry by John La Roche

Acknowledgements: Thanks to David Wilton, Russell Skeet and John Isdale for their assistance.

Page last updated: 07 November 2019