Women’s groups were gaining traction in official circles; government campaigns encouraged women to enter non-traditional jobs; more women were attending university and universities became more active in trying to attract women to their engineering degree courses. Women engineering student numbers moved from 2 percent to 12 percent but numbers of women in the engineering profession remained low.

Campaigns to expand the range of jobs considered acceptable for women

In 1983 just over half of women in the paid workforce were in secretarial, clerical, teaching, nursing, clothing or sales jobs. An area the women’s movement had its eye on was expanding the range of jobs considered acceptable for women. Through the 1980s, the Women’s Advisory Committee of the Vocational Training Council ran campaigns and produced booklets, posters and kits all aimed at promoting and supporting women into non-traditional work. This included trades and in particular engineering related trades which had always been almost exclusively male.

Girl’s Can Do Anything was the slogan of a public education campaign, run by the Vocational Training Council from June – August 1983, and became a catchphrase of the 1980s. The campaign aimed to break down stereotypes of men’s and women’s work and to give women the confidence to enter male dominated sectors. The programme did not expect immediate dramatic results, but instead focused on building public awareness as a prerequisite for long-term change. Campaign materials included posters and television ads showing women succeeding in male dominated industries and trades; a series of radio interviews with women in non-traditional jobs; a NZ Women’s Weekly reader survey of women in non-traditional work; and resources for careers advisors and schools. Throughout the 1980s, the Vocational Training Council, under the Labour Department’s Positive Action Programme for Women, continued to produce publicity material and resources for schools and careers advisors and to support women into apprenticeships.

While the focus of the Vocational Training Council’s campaign was apprenticeships and trades training, it revealed issues common to professional engineering as well, namely women’s lack of prerequisite knowledge to enable them to enter tertiary engineering courses, and social resistance to women entering male-dominated workplaces. In 1981 the Manukau Technical Institute, supported by the Education Department and the Vocational Guidance Council, piloted a 12-week course, “Basic Engineering Skills for Young Women” as an entry point for women into trade-level engineering roles. Nine women completed the course. Their responses to the post-course survey reveal that they enjoyed the course but were dismayed by the attitudes shown by potential employers or the basic repetitive work they were given. One woman was told at a job interview that they didn’t have toilets or changing rooms for women and that women always get pregnant. However, not all employers were hesitant to take on women. In 1981, NZ Forest products Ltd welcomed its first five women apprentices at its mill in Kinleith and were actively looking to recruit more. And in 1982, the first women were employed in construction roles on the Marsden Point Oil Refinery expansion.

Tutor Peter Shapcott demonstrates a welding torch to students on Manukau Technical Institute’s engineering skills course for young women, 1981. The course was the first of its kind in the country. Photo: © Stuff Limited

As well as its work on trade training, the Vocational Training Council also collaborated on programmes to promote professional engineering to women. In 1981, the Council supported a visit by women engineers to Wellington Girls’ College where they spoke to Form 4 (Year 10) students about their jobs and professional engineering as a career. The Vocational Training Council also supported the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research (DSIR) on its own Women into Engineering campaign. In 1988 only 10 percent of DSIR scientists were women. From 1987 the DSIR began offering 11 study grants a year to women wanting to train in the sciences, in particular, physics and engineering.

Universities

Throughout the 1970s, the percentage of women attending university increased, and by 1980 was sitting at around 40 percent. The faculties of law and medicine had both seen significant increases in the number of women enrolling, reaching 20 percent by 1980. In engineering, female enrolments at Auckland and Canterbury sat around 2 percent. This prompted university engineering departments to have a harder look at the culture of the school and the pathways into professional engineering education.

At the beginning of the 1980s engineering schools were still a largely mono-cultural environment and a hard place for anyone who was different. At University of Auckland the laddish culture of pranks, heavy drinking, obscene songs, and blue movies that had developed when the school was out at Ardmore lingered into the 1980s. A survey of female engineering students at University of Auckland in 1982 provided insight into the student experience and some of the challenges women faced. It revealed that pathways into engineering for women often came down to chance. Careers advisors, teachers and parents did not know enough about engineering and the diverse career possibilities it offered and did not encourage girls to consider it. On the whole, survey respondents enjoyed their time in the engineering school but also reported feeling conscious of standing out – never being able to disappear into the crowd and feeling greater pressure to do well. They also noted that boys had more informal networks available to them. Finding practical work experience was harder for women students – encountering sexual discrimination when applying for summer work experience was not uncommon. They also raised the issue of the insufficient number of female toilets in the engineering school. These were common issues and not limited to University of Auckland. Female engineering students at University of Canterbury who responded to a survey expressed similar feelings of discomfort in classes dominated by males and reported the persistent use of gendered language and sexist jokes on the part of some lecturers.

Students completing hands-on activities at University of Auckland’s Enginuity Day, 1990s. Photos: Liz Godfrey/University of Auckland

University of Auckland

In the 1980s the University of Auckland increased its efforts to attract female students to the engineering faculty. The Women in Engineering and Schools Liaison Committees continued to run Enginuity Day, begun in the late 1970s, and to build connections with high school teachers. But with only a small group of staff committed to the cause it could only ever be a part-time effort.

In 1989, the University received money from a contestable government fund to establish the position of Liaison Officer for women in engineering and physical sciences. It was the first position of its kind in the country. The successful applicant was Liz Godfrey, a former high school teacher and University of Auckland chemistry lecturer. Her appointment brought new vigour to the university’s efforts and support for women students. Rebecca Ronald, an engineering student at University of Auckland from 1988–1993, recalled that Liz’s door was always open to students to discuss any issue big or small or just to chat. The Dean of Engineering, Raymond (Ray) Meyer, was supportive of Liz’s role and allocated money in the department’s budget to continue the programme beyond its initial funding.

Liz continued to grow Enginuity Day and began a new programme SOS: Skills and Opportunities in Science, in late 1989. SOS was a joint initiative developed by Liz Godfrey, Bev Farmer (Auckland College of Education), and Lorraine McCowan (Auckland Girls’ Grammar). The programme was aimed at 12–15-year-old girls to catch their interest in STEM before they opted out of maths and science subjects. The programme ran as a series of seminars over two days, with women engineers facilitating job-related problem-solving activities. By 1992 the programme was running in both the North and South Islands, with local teams of teachers acting as advisers. The seminars aimed to show the relevance of science to the students’ lives. The involvement of early career professionals showed women succeeding in exciting engineering roles where teamwork, communication skills and creative thinking were valued alongside technical knowledge. As a follow up to the programme, posters showing women working in a variety of science and technology roles were distributed to every secondary school in the country.

To build a collaborative network and pool of women who could support the Enginuity Day and SOS programmes, Liz helped to establish the Association of Women engineers. The group ran social and professional development events for its members and sometimes invited guest speakers. The group was slow to become established. Gretchen Kivell recalled the group took three attempts to get going in its early years. She reflected that joining this kind of group “was unattractive to many of the early women engineers because they had worked so hard to become engineers, and they didn’t want anything that set them apart. They just wanted to get on with being engineers.”

University of Canterbury

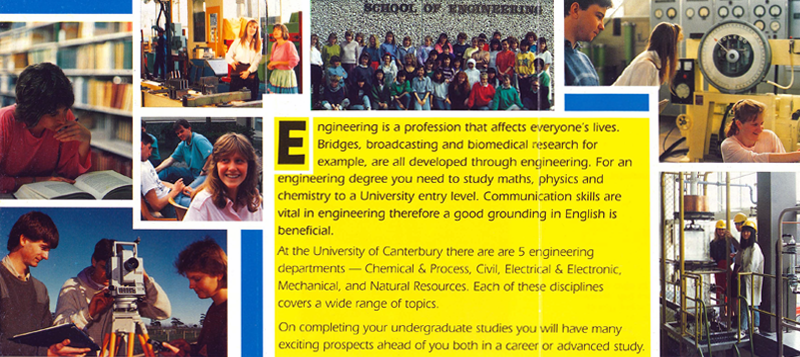

From the early 1980s, the University of Canterbury ran similar initiatives to those developed in Auckland. From 1982, the Engineering Faculty’s Schools Liaison Committee held a Schools Visit Day where students and teachers from high schools in the South and lower North Islands were invited to tour the engineering school, see displays of laboratory equipment and research projects and to talk with staff, students and graduates. In particular, the faculty was hoping to inspire female students, and from 1983 also ran a series of Women in Engineering seminars for high school students. The seminars took the form of a panel discussion with women engineers at different career stages discussing their work and experience.

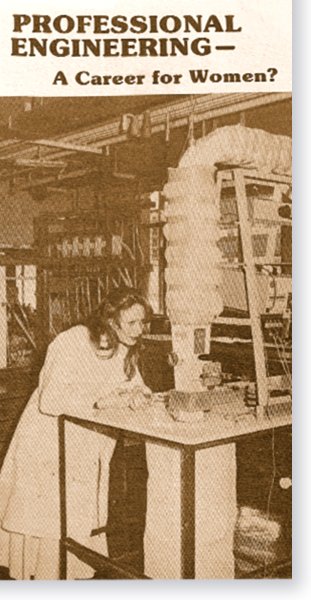

The faculty’s Schools Liaison Committee also produced a brochure: ‘Professional Engineering – a career for women?’ The brochure reassured prospective female students that although the “number of women engineering students is still relatively few…it is very unlikely that you ever encounter any prejudice on the part of staff or other students, and in fact you will probably find them particularly friendly and helpful.” Unfortunately, however, this statement did not entirely align with the experience of all students. As an undergraduate student in 1984 about to enter her first professional year and looking to choose a discipline, Catherine Watson met with the mechanical engineering Head of Department, only to be told “Women don’t do mechanical [engineering].” This was despite the department having the faculty’s only woman academic staff member at that time – Dr Anne Ditcher, who had been a lecturer in the department since 1981. In 1984 Anne established a Women Engineers Group. At this time, the group was little more than a mailing list of women engineers to support the university’s schools outreach programme. Evidence from the time suggests that Anne likely received little support from her Head of Department to develop the group further.

Brochure produced by University of Canterbury in the early 1980s and distributed to high schools. Image: R2241073, Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga, Wellington

In 1988, a small group of students, including Catherine Watson, then beginning her PhD, started up a Women in Engineering group for students. The group’s activities at this time included informal meetups and the occasional speaker, contacted through the Association of Women Engineers. Catherine recalled that some male engineering students felt very threatened by the group and on one occasion broke in and trashed the meeting room used by the Women in Engineering group. Faculty staff assumed the women had trashed the room and made moves to shut the group down. The group protested and cited the faculty’s tolerance for the drunken activities of male students. Male students eventually confessed to trashing the room and the women’s group was allowed to remain.

In 1989 the Women in Engineering group produced its own, much more colourful, brochure showing women students working on projects across the university’s engineering disciplines.

Brochure produced by the University of Canterbury Women in Engineering group, 1989. Image: University of Canterbury

Challenges for universities

The increasing interest in supporting women students and the initiatives begun during the 1980s heralded positive change but there were still challenges. In 1989, Liz Godfrey ran a second student survey and compared the results to those collected in 1982. She found that female engineering students now came from a wider range of high schools and backgrounds but that many of the challenges identified in 1982 were still in play. There was still a lack of information at high schools about engineering careers and a lack of understanding of what professional engineering work involved. Recruiting female academic staff was another challenge for universities. In 1973, the University of Auckland engineering school had a part-time female lecturer, Dr Mary Farmer, on staff and had just employed its first woman laboratory technician. In 1975, Sue Truman became the school’s first fulltime woman academic staff member when she was appointed as a junior lecturer. In 1988 the faculty had one woman member of academic staff – in the department of Theoretical and Applied Mechanics. Dean of Engineering Raymond (Ray) Meyer expressed his desire to recruit more women but faced a lack of female candidates. In 1987 at the University of Canterbury women made up 4 percent of engineering students and 3 percent of faculty staff.

IPENZ

At the 1981 IPENZ conference the NZ Herald reported that “Seven women engineers joined about 800 men at their profession’s annual conference in Auckland.” A few years later the numbers had not improved. In 1984 IPENZ had 5,700 corporate members, 11 of whom were women, and 17 women graduate members. Through the 1980s IPENZ took a closer look at the experience of its women members and considered what the Institution had to offer them and what it could do to support them. The Institution would also have to prove that it valued diversity and did not see women only as a largely untapped pool from which to make up the shortfall of engineers New Zealand needed.

Getting more young people interested in a career in engineering had long been a concern of IPENZ. In 1961 it started the Dobson Lecture Series. Leading engineers visited high schools in main centres and towns across the country and presented a lecture on a topic aimed to inspire their young audience. Early topics included “Power for the Nation”, “This World of Wheels” and “The Jet Age”. A brochure on engineering careers was then handed out. From 1974 the lectures were aimed at a wider audience and “enhanced the standing of the Institution generally” and the organising committee began to look at other ways to promote engineering to students. The committee transitioned to become the Schools Liaison Committee, officially changing its name in 1985. The last Dobson Lecture was given that same year. From the early 1980s the committee focused its attention on promoting engineering as a suitable career for girls. In collaboration with University of Auckland, IPENZ produced two 20-minute videos aimed at high school students. The committee also continued its programme of school visits, with engineers giving more relaxed and personal talks about their work rather than formal lectures.

E.W de Lisle presents the 1963 Dobson lecture, “Communications for the Nation”, to secondary school students. Photo: Engineering New Zealand Auckland Branch

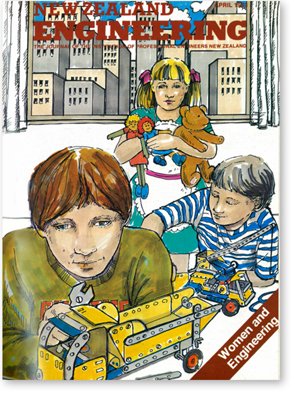

In 1983, IPENZ devoted the cover story of the April edition of its magazine, New Zealand Engineering, to the issue of women’s low representation. The article identified the poor public image of engineering as dirty, heavy work that involved machines rather than people; girls’ subject choices at high school; and societal pressures, including the attitudes of careers advisors, parents and employers, as reasons for women’s under-representation in the profession.

Women played a leading role in changes within IPENZ. From 1982–1984, chemical engineer, Gretchen Kivell, served as convenor of the Schools Liaison Committee – becoming the first women to lead an IPENZ committee. In 1984, Gretchen was the first woman to lead an IPENZ Branch committee. She joined the IPENZ Governing Board in 1988 and became the Institution’s first woman president in 1998. Gretchen took issue with the institution’s ingrained use of gendered language. She wasn’t the only one to feel that way. The issue was first raised in a letter to the editor in 1981, upbraiding the Institution for its universal use of the pronouns ‘he’ and ‘him’ when referring to its members and to engineers more generally. No formal action was taken on this issue until 1988 when the Association of Women Engineers put forward a proposal at the national IPENZ conference for IPENZ to: 1. Promote engineering as a career for women, with a particular focus on encouraging Form 3 and 4 (Year 9 and 10) girls to continue with maths and science subjects; 2. to promote equal opportunity employment; and 3. To redraft the institution’s Code of Ethics to remove sexist language. These resolutions were adopted and changes to the Code of Ethics made the following year.

Cover of the April 1983 issue of New Zealand Engineering magazine, promoting a feature article about women in engineering. Image: Engineering New Zealand

Also at the 1988 conference, was a session organised by the Electrical Engineering Advisory Council (EEAC) “to explore issues arising as increasing numbers of women enter the engineering profession.” A panel of four women engineers, chaired by Dr Mary Earle discussed societal expectations around men’s and women’s work and perceptions of what engineering work involved; girl’s subject choices at high school; maternity leave and re-entering the workforce.

Following the 1988 conference, IPENZ’s Executive Director, A J Bartlett, dedicated his editorial in New Zealand Engineering to celebrating the Institution’s work so far on welcoming women into the profession. He noted that women were needed in the profession, not only to increase the number of engineers, but also for the “particular contribution that women can make to engineering. The profession needs a greater input of awareness of people and their needs — an awareness more generally characteristic, it can be said, of women than of men.” This broadening awareness from a focus on numbers to recognition of women’s unique contribution to the profession laid the foundation for the work of the following decades.

Conclusion

The initiatives of the 1980s saw women’s enrolment in engineering degree courses move from 2 percent to hover around 12–13 percent by the end of the decade. With more women entering the profession, the focus of the next decade would expand from recruitment to university courses, to women’s experience in the workplace.

Growth in the 1990s

In the 1990s, attention turned to women’s experience in the workplace. More women were graduating as engineers but were more likely than men to leave the profession.