By the end of the decade, this had risen slightly, to sit around 3–4 percent. The majority of these women – 73 percent – were under the age of 34. More young women were entering the profession but were less likely than men to stay. Through the 1990s the conversations around women in engineering broadened. From an initial focus on increasing the number of women entering tertiary engineering courses, conversation began to consider women’s experience in the workplace, covering topics such as organisational culture, parental leave policies, part-time work and promotion.

Universities

During the 1990s, the percentage of female engineering students at the two main engineering schools – Auckland and Canterbury – increased from around 12 percent, to hover between 16–20 percent by the end of the decade.

University of Auckland

At the University of Auckland, the SOS programme established by Liz Godfrey in 1989 continued to receive a positive response from students and teachers. To extend the programme’s reach and impact, a work pack of suggested classroom activities was distributed to teachers. A training video was also developed to help schools gain sponsors and to run their own SOS events in their region.

The now well-established, Enginuity Day was the other key event in the engineering school’s promotional programme. Enginuity Day was open to girls in their last two years of high school studying maths, chemistry and physics. Hands-on activities and the opportunity to talk to practicing women engineers made the day popular and it was regularly oversubscribed. In 1998 the event attracted 170 Form 6 and 7 (Year 12 and 13) students from 49 different high school across the Auckland region.

A girls-only careers day was another opportunity for high school students to visit the engineering school to learn more about the disciplines offered. The participation of female undergraduate engineering students was an important feature of these open days. Undergraduate students were also encouraged to visit their old high schools to give talks about the engineering school and their study experience.

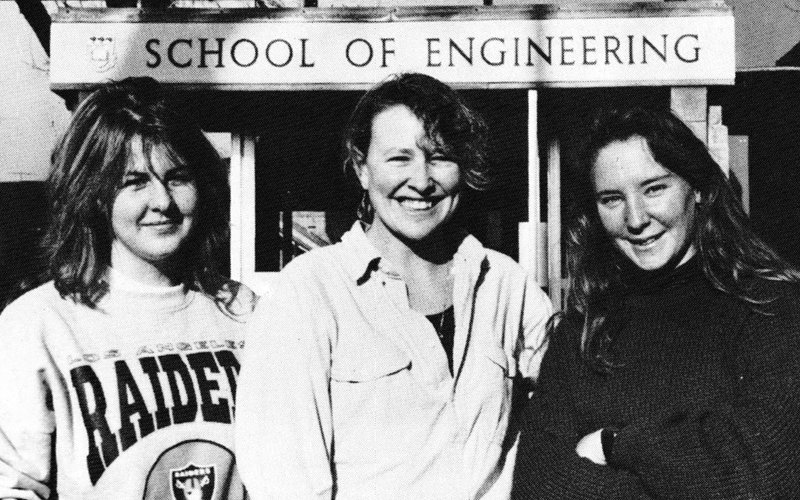

In 1992 Kirsten Arthur, Lou Wickham and Rebecca Ronald (pictured left to right) led the formal establishment of University of Auckland’s Women in Engineering Network. Photo: University of Auckland

In 1992, engineering students Rebecca Ronald, Lou (then Louise) Wickham and Kirsten Arthur led the formal establishment of the University of Auckland’s Women in Engineering Network (WEN). At the time, Rebecca was Engineering Students’ Association President – the first woman to serve in this role. Lou was the Engineering Students’ Association Women’s Affairs Officer and Kirsten, the fourth-year chemical and materials engineering class representative. Inspired by overseas programmes, their aim was to establish a group where female engineering students could find peer support and social connection, information about the engineering industry, and could support the engineering faculty in its outreach activities to schools. In the years before 1992, the group’s activities had included informal peer tutoring, shared lunches and school visits. General support and advice had also been provided by Liz Godfrey, Liaison Officer for women in engineering and physical sciences. In 1993, Rosalind Archer, then in her final year of undergraduate studies, took a leading role as co-president of the group. She recalled that the group’s activities at this time included student-led tutorials, the publication of a ‘beginners guide to engineering school’ booklet with tips and tricks, and talks from professional engineers. The formal establishment of WEN in 1993 was an important endorsement of the faculty’s women students. By the end of the 1990s, the combined efforts of women students along with male allies, Liz Godfrey and the school’s Dean, Roy Sharp, had achieved an important cultural shift. This was evident in improved behaviour at Engineering Students’ Association events, and in promotional material for the school which emphasised the people side of engineering work and showed women as active researchers doing challenging and exciting work.

Bachelor of Engineering Science graduates from University of Auckland, 1993–4. The top five graduates in Engineering Science were women. Photo: Liz Godfrey/University of Auckland

University of Canterbury

In the 1990s, the University of Canterbury stepped up its efforts to promote the engineering school to perspective female students and to do more to understand the barriers preventing greater interest and uptake from female high school leavers.

In 1991, the university was awarded $30,000 from the Ministry of Education’s Contestable Equity Fund to kickstart a programme developed by the university called Women into Professional Engineering. The programme was supported by Associate Dean of Engineering, John Abrahamson, who was also the Chair of the IPENZ Schools Liaison Committee. Elizabeth (Liz) Roxborough was employed as co-ordinator of the project and began work in May 1991. Liz interviewed engineering students, practicing engineers, teachers and the public about their experience in or knowledge of professional engineering as a career. The results of the interviews confirmed the continued existence of social expectations and attitudes that were biased against girls entering or continuing in STEM subjects, and a lack of knowledge on the part of parents, teachers and careers advisors about the work of professional engineers in different disciplines. This informed the decision to first focus time and energy on connecting with high school maths and science teachers and careers advisors. By December 1993 over 200 teachers had attended nine seminars held around the country where they heard from male and female engineers from a range of disciplines, backgrounds and career stages. A video and other resource material were also provided to schools along with the encouragement to invite local engineers to speak in their classrooms. Many of these programmes relied on the participation of women engineering students and professionals.

The University’s Women in Engineering group (WiE) was formally established in 1999. Prior to this, a Women in Engineering group waxed and waned according to the interest and availability of students to run it. The Women in Engineering Group formed by students in 1988 continued to run activities into the early 1990s. In September 1990, the group organised an end of year dinner attended by some fifty women. Attendees were a mix of engineers and DSIR science study award recipients. Sharee McNab had attended Women in Engineering group events during her time as an undergraduate student, 1990-1993. But by the time she returned to University of Canterbury in 1997 to complete a PhD in electrical and electronics engineering, the group seemed to have fallen away. Sharee restarted the group the following year. The group ran casual get togethers, such as potluck dinners, providing an opportunity for students from different disciplines to connect. The group had a good turnout for events and was valued by those who came along. Electrical Engineering student, Kate Macdonald (née McCarroll) was an enthusiastic member of the group. She joined the committee in 1998 in her first pro year and then took on the leadership of the group for her final two years at university. In 1999, the group ran a popular Engineering in Schools programme where WiE members visited local high schools to talk to Form 4 (Year 10) students about engineering. The group’s momentum continued the following year with sponsorship from five local engineering firms and support and encouragement from Dean of Engineering, Alex Sutherland.

Sharee McNab at the Women in Engineering group sign-up table, University of Canterbury clubs’ day, 1998. Photo: Sharee McNab

Other university courses

Outside of the main engineering schools of Auckland and Canterbury, other engineering courses were attracting significantly higher percentages of female students. Massey University’s food technology programme, begun in the 1960s, had always attracted high numbers of women and by the 1990s was regularly seeing 50 percent female enrolments. The chemical technology course was also popular, with around 45 percent female enrolments. In 1998, Auckland Institute of Technology launched its Bachelor of Engineering Degree. It included the option to study environmental engineering, an emerging field at that time. This course in particular attracted high numbers of women students, approaching as much as 40 percent. In 2000, the University of Waikato introduced a four-year Bachelor of Engineering with honours programme. As at other universities, chemical and environmental engineering proved the most popular specialisations for women.

IPENZ

In 1984 less than 0.5 percent of IPENZ members were women. By 1998 this figure had increased only slightly to 1.7 percent, with half of these members in the graduate category. Through the 1990s IPENZ published more articles in its magazine, New Zealand Engineering, profiling women engineers and giving voice to women’s issues, and towards the end of the decade began to tackle the more complex topics of workplace culture, balancing work and family life, and women’s contribution to the profession.

Through the 1990s women IPENZ members held a Women in Engineering Forum at the annual national conference. This photo was taken at the 1994 conference in Nelson. IPENZ's first female President, Gretchen Kivell, sits front left. Photo: Engineering New Zealand

1993 was the centenary year of women’s suffrage in New Zealand. IPENZ marked the occasion by honouring five women for their individual achievement and contribution to the profession. Certificates were awarded to Jenny Culliford (representing practicing women engineers), Mary Earle (representing women engineers in the academic world), Barbara Elliston (representing women engineers in management and industry), Pat McCook (representing pioneering women engineers), and Gretchen Kivell (representing women engineers in IPENZ). That same year Gretchen was also conferred Fellow of IPENZ – the first woman to achieve this honoured membership class. The coverage of the centenary awards in New Zealand Engineering was largely celebratory in tone, but also touched on some of the challenges faced by women engineers in the early 1990s, including balancing work and family life.

In 1995, as a graduate engineer and just prior to embarking on the mandatory OE, Lou (then Louise) Wickham wrote an article for New Zealand Engineering discussing the pervasive and covert sexism they and their peers faced working in engineering consultancies. The article called out the yawning gap between companies’ equal employment opportunity policies and what was happening in practice. At their firm, a company of over 100 employees, there were no women in senior management roles. Not, Lou wrote, because there weren’t any women to promote, “but because senior (male) management doesn’t want them there.” The article was published anonymously, for fear of career retribution. When their name as author did get out, Lou was told they were blacklisted. Lou went and worked overseas, only returning to New Zealand in 2004, by which time the matter was long forgotten.

In 1998, IPENZ elected its first female President – Gretchen Kivell. Gretchen was an active member of IPENZ, having been Convenor of the Schools Liaison Committee and Chair of the Auckland Branch. Gretchen wrote articles for the IPENZ magazine drawing attention to the challenges faced by women engineers. “Currently engineering is a full-time, full-career profession with little tolerance for career breaks,” she wrote in 1998. That same year, Gretchen collaborated with Liz Godfrey, Liaison Officer for women in engineering and physical sciences at University of Auckland, on a questionnaire, sent to members of the Association of Women Engineers. The Association, first formed in the late 1980s had taken a while to gain support and become established, but by 1998 had over 300 members across its regional groups who met to socialise and discuss professional issues. The results of the questionnaire provided insights into women’s experiences in the workplace. On the whole, the women who responded to the questionnaire enjoyed their work, citing the variety, challenge, satisfaction of solving problems, and feeling that they were making a difference. Balancing work and family life was important to the respondents, but very few felt that they had successfully accomplished a career break. Part-time or alternate working arrangements, professional development and salaries were also identified as issues they would like to see receive greater attention and discussion. Some also expressed that while they loved their work, because of some of their own experiences, they felt hesitant to encourage women into the profession. More than half of the survey respondents were not IPENZ members. Reasons for not joining included the perception of IPENZ as a “civil old boys club” and not relevant to their discipline. They wanted to see events for younger engineers of all disciplines and an open forum to discuss issues such as parental leave and flexible working. They also had a “plea to branch and function organisers - please don’t assume all engineers are Mr and that ‘suitable dress’ is a ‘jacket and tie.’”

Conclusion

In the 1990s the conversations about women in engineering opened and shifted away from the previous focus on recruitment into tertiary engineering courses to include discussion of women’s experience in the workplace. This was a significant shift and opened the path for further change in the following decade.

Workplace experience in the 2000s

In the 2000s, workplace culture and the value of diversity were widely discussed. Companies sought to retain women in the profession.