But it was not until the second half of the twentieth century that women graduated from New Zealand universities with engineering degrees.

Women’s attendance at New Zealand universities

University education in New Zealand began in the early 1870s. There was never any restriction on women’s enrolment, and a few women soon began to attend. The first to enrol was Helen Connon who began attending classes at Canterbury College in 1875 and graduated with a BA in 1880. Kate Edger completed her studies in Auckland and gained her BA a few years before Helen in 1877, making her the first woman to graduate from a New Zealand university.

Ethel Benjamin, centre front, with other lawyers at the opening of the Supreme Court in Dunedin, 1902. Photo: Hocken Collections, Reference Number: Box-235-003

The first women medical graduates were Emily Siedeberg and Margaret Cruichshank who graduated in 1896 and 1897, with Margaret becoming the first female doctor to register in New Zealand. In 1897 Ethel Benjamin was the first woman to graduate with a law degree and to be admitted as a barrister and solicitor of the Supreme Court of New Zealand. Despite members of the Otago District Law Society attempting to exclude her, Ethel established a successful practice as a barrister and solicitor.

These early successes aside, women’s participation in higher education was looked upon by many in New Zealand society with some disapproval. Child health reformer Truby King argued that too much study could impair women’s reproductive abilities. Differences in the subjects taught to girls and boys at primary and secondary level also discouraged women from tertiary education and steered them away from maths and science subjects. School subjects were designed to prepare girls for their future roles as wives and mothers. In 1917 compulsory home science was introduced for Form 3 and 4 (Year 9 and 10) girls – a situation that would remain unchanged until 1942 – with the result that other science subjects were less available to girls. For Forms 1 and 2 (Years 7 and 8), woodwork was for boys and home craft for girls. This division was in place from 1929 until the 1970s when, finally, both girls and boys could take cooking, sewing, woodwork and metalwork.

Girls in a home science cooking class, circa 1939. Photo: Green & Hahn. Making New Zealand: Negatives and prints from the Making New Zealand Centennial collection. Ref: PAColl-8550-08. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

Women in the workforce

In the late nineteenth century, women in full-time employment made up about 18 percent of the labour force. During the First World War, women were called upon to fill positions vacated by men serving overseas and temporarily found employment in non-traditional roles. In 1933, women’s employment at an engineering workshop in Christchurch was still unusual enough to make the news. The Evening Post reported that three women were starting work at Anderson’s Ltd where they would be “employed on light work, such as casting, drilling, and core making…” There was no shortage of women interested in the roles, which attracted 60 applicants.

Anthea Abercrombie working at the Dominion Physical Laboratory, Gracefield, Lower Hutt, Wellington, circa 13 May 1943. Photo: Pascoe, John Dobree, 1908–1972: Photographic albums, prints and negatives. Ref: 1/4-000429-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

Although there was no restriction to prevent women enrolling in engineering courses, they were effectively barred by social expectation. In the 1930s, Sybil Lupp wanted to develop a career as a mechanical engineer, but her parents did not consider this a suitable occupation for a woman. Pursuing her interest in cars, she tried, secretly, to find work in a garage, but none would employ her. By the 1950s however, she had managed to establish her own mechanical workshop specialising in high performance cars.

During World War II, women’s employment as a percentage of the labour force peaked briefly to 25 percent before falling again, almost to pre-war levels. In the 1950s, the question of whether it was appropriate for married women and mothers to work in paid employment was hotly debated. Women’s participation in the work force grew only very slowly during the 1950s, and was still under 25 percent by the end of the decade. It then increased steadily to reach 34 percent in 1981. Still, despite more women entering the workforce, the types of jobs available to them continued to be limited, with the most common occupations being nursing, teaching, shop and clerical work and food and clothing production.

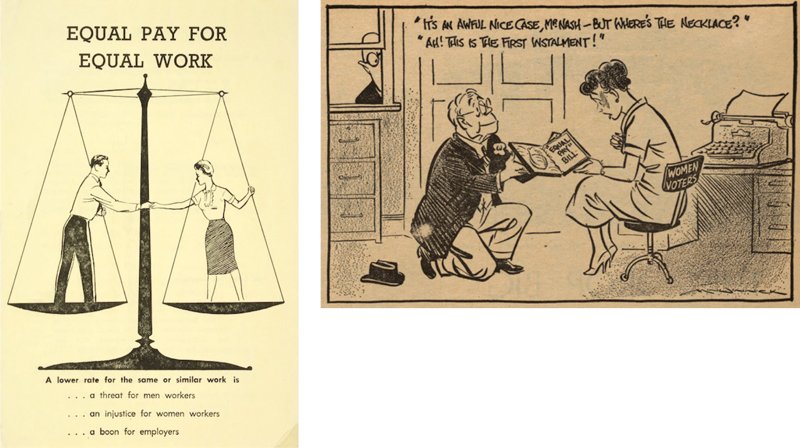

Through the 1950s, women’s groups campaigned hard for equal pay for public service roles. The Government Service Equal Pay Act passed in 1960 and was phased in over the following five years. It was a step in the right direction, but there was still much to do.

Left: Equal work for equal pay poster, produced by the Council for Equal Pay and Opportunity, 1961. Ref: Eph-A-WOMEN-1961-01. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. Right: Cartoon from 1960, satirising the staged introduction of equal pay for the public service. Prime Minister Walter Nash offers women voters an “awful nice case” with nothing in it. Image: Auckland Weekly News, Reference: AWN26.10.1960 p. 6

Conclusion

From the mid-1870s, women were forging a place in university education, but it would be another 90 years before women would graduate from New Zealand universities with engineering degrees. In the mid-twentieth century, women’s career options were still limited by training opportunities and social expectation.